Overview

Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder (HSD) describes symptomatic joint hypermobility with musculoskeletal (and sometimes systemic) consequences in people who do not meet the 2017 diagnostic criteria for hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (hEDS) or another heritable connective-tissue disorder (HCTD). Prevalence of generalised joint hypermobility varies (≈2–35% depending on age/sex/ethnicity and cut-offs), with symptomatic states more common in females and in younger people; many present to primary care, sports, pain and rheumatology settings.

Definition

Joint hypermobility: increased physiological range of motion compared with age/sex norms; may be localised, peripheral or generalised.

Beighton score: 9-point bedside measure of hypermobility; age-/sex-adjusted thresholds used in 2017 framework (see Table 1)

Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder: symptomatic hypermobility with musculoskeletal complications (e.g., pain, instability, recurrent soft-tissue injuries) that does not satisfy 2017 hEDS or another HCTD diagnosis; subtyped as Generalised-, Peripheral-, Localised-, or Historical-HSD.

Five-part questionnaire (5PQ): historical screen for hypermobility; ≥2 positive answers supports GJH when Beighton is borderline.

Anatomy & Physiology

- Connective tissue microanatomy: collagen I/III and elastin form fibrillar networks in capsules, ligaments and tendons; tenocytes and fibroblasts remodel ECM in response to load.

- Proprioception & motor control: mechanoreceptors in ligaments, muscle spindles and joint capsules drive reflexive stability; peri-articular muscle strength and neuromotor timing protect end-range positions.

- Load–tolerance: bone, cartilage and tendon adapt to graded load; rapid load spikes or end-range repetition exceed tissue capacity

In hypermobility, sensorimotor control often matters more than static laxity—training targets timing, endurance and control rather than “stretching”.

Aetiology and Risk Factors

Aetiology

- Constitutional joint laxity (polygenic background distinct from monogenic HCTDs

- Tissue factors: relatively compliant collagen/ECM; reduced passive stiffness; impaired proprioception and muscle endurance

- Systems factors: autonomic dysregulation (orthostatic intolerance/POTS) and central pain amplification may contribute to symptom severity in a subset

Risk factors

- Female sex

- Younger age

- Family history of JH

- High training volume in flexibility sports (dance/gymnastics).

- Deconditioning

- Prior sprain/dislocation

- High pain catastrophising or fear of movement

- Poor sleep

- Anxiety/depression\

- Coexistent dysautonomia or GI dysmotility

Marked skin fragility, atrophic scarring, marfanoid habitus, lens/valvular disease, or aortic pathology should redirect evaluation toward hEDS/EDS subtypes, Marfan or Loeys–Dietz rather than HSD.

Pathophysiology

- Baseline laxity ± impaired proprioception → increased end-range exposure and micro-instability.

- Recurrent minor injury and pain → guarded movement, deconditioning and muscle endurance deficits.

- Central factors (nociplastic pain, autonomic symptoms, sleep disturbance) sustain symptom generalisation and fatigue in a subset

- Behavioural adaptations (avoidance, bracing overuse) can perpetuate weakness and instability unless retrained.

Load mismatch (capacity < demand) explains many flares—progress load gradually and favour control over range.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients may present with localised symptomatic hypermobility (e.g., affecting one or two joints) or generalised hypermobility with widespread pain and systemic features.

- Musculoskeletal: chronic activity-related pain (knees, shoulders, ankles, spine), recurrent sprains/“giving way,” subluxations/dislocations, tendinopathies, patellofemoral pain, pes planus, early fatigue with tasks, delayed recovery; myofascial trigger points.

- Functional: poor endurance, reduced balance/proprioception, clumsiness, kinesiophobia; difficulty with sustained postures (standing, desk work).

- Autonomic/GI (subset): orthostatic intolerance or POTS (light-headedness, palpitations), thermoregulatory complaints; functional GI symptoms (early satiety, bloating, constipation)

- Skin/soft tissue (usually mild vs hEDS): soft/velvety skin, striae, easy bruising, hernias/pelvic floor symptoms; not the marked atrophic scarring of classical EDS

Clinical Examination

- Generalised or regional hypermobility (Beighton/other joints)

- Tenderness at peri-articular structures

- Dynamic valgus/poor control on functional tasks (single-leg squat, step-down)

- Normal neurology

- Exclude synovitis.

Triad: Hypermobile joints + Activity-related pain/instability + Functional fatigue/deconditioning.

Diagnosis

HDS is based on Beighton score (for joint hypermobility) and exclusion of other connective tissue disorders.

2023 paediatric framework separates paediatric generalised hypermobility and uses age-appropriate assessment, deferring definitive hEDS labelling until biological maturity; symptomatic children are managed with the same principles as HSD.

Differential diagnosis

- hEDS/other EDS types

- Marfan/Loeys–Dietz

- Neuromuscular hypotonia

- Inflammatory arthritis (RA/JIA)

- Shoulder/knee instability from labral/ligament tears

- Chronic widespread pain/fibromyalgia

- Functional neurological disorder (if mismatch of symptoms and motor exam).

Marked skin fragility/atrophic scars, aortic root dilatation, lens dislocation, or severe periodontal disease are not typical of HSD—seek genetics/cardiology where present .

Treatment

HSD is not benign joint laxity—it sits on a continuum between physiological flexibility and heritable connective tissue syndromes. Recognition is important because early rehabilitation and lifestyle modifications can reduce long-term pain and disability.

- Education & self-management

- Explain benign nature of laxity

- Flare management

- Pacing

- Sleep optimisation

- Address kinesiophobia and catastrophising

- Physiotherapy (cornerstone) / Exercise physiologist

- Progressive strengthening (hips/shoulders/core)

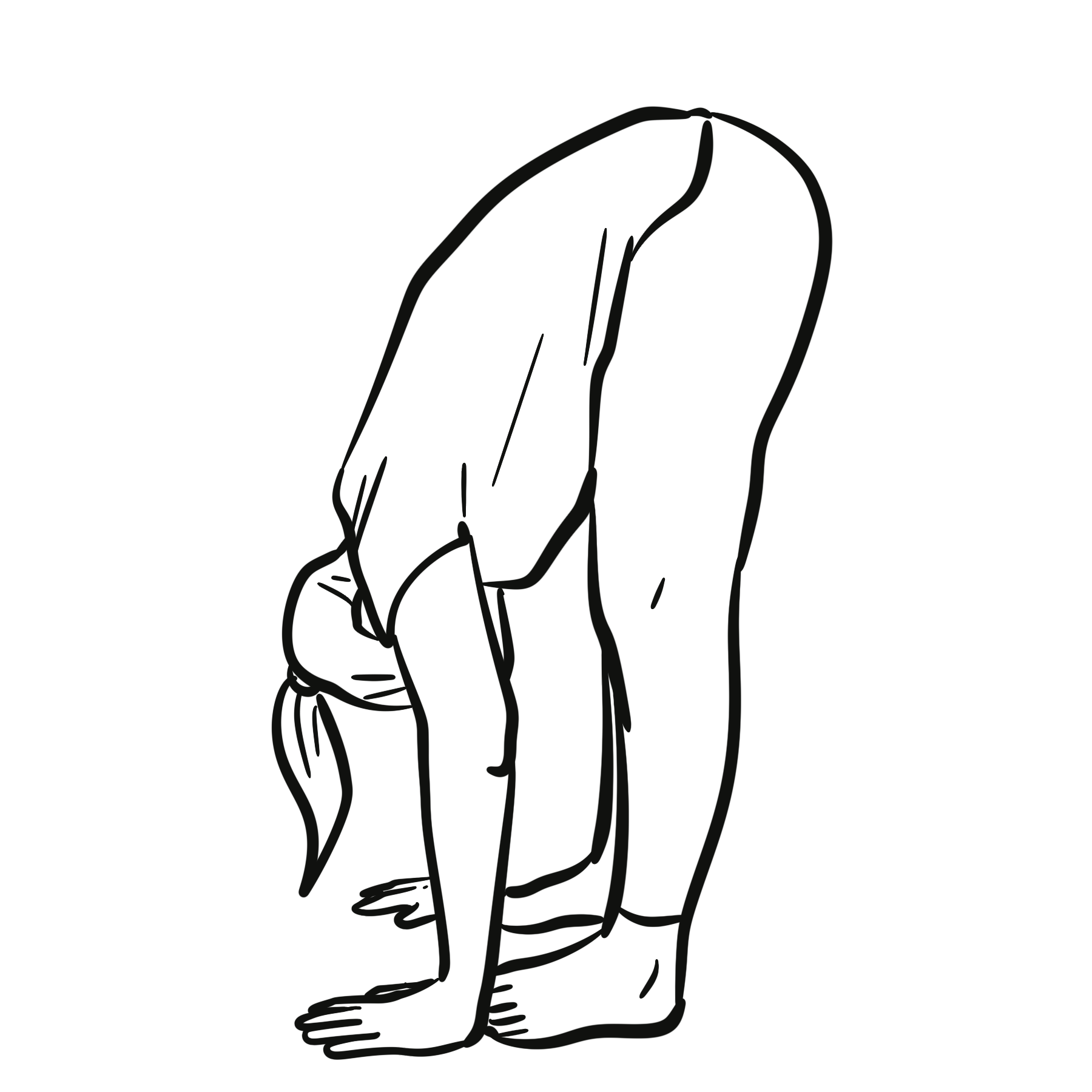

- Motor-control/proprioceptive training

- Closed-chain exercises

- Balance work

- Technique coaching to avoid end-range loading; gradual return-to-sport

- Activity & load management

- Graded activity with symptom-contingent progression

- Reduce repetitive end-range tasks

- Task modification at school/work.

- Adjuncts

- External supports (taping, braces, compression garments) short-term for high-risk tasks

- Foot orthoses for pes planus

- Ergonomic advice

- Pain management

- Consider TCAs/SNRIs or gabapentinoids for nociplastic features

- Topical NSAIDs for focal tendinopathy

- Avoid long-term opioids

- Treat sleep disturbance and mood comorbidity

- Autonomic/POTS (if present)

Strength + motor control gains are dose-dependent—consistency trumps intensity; write plans patients can actually keep.

Complications and Prognosis

Complications

- Recurrent sprains/subluxations

- Tendinopathy

- Patellofemoral pain

- Early osteoarthritis risk in unstable joints

- Chronic pain with reduced activity

- Autonomic intolerance (subset)

- Pelvic floor disorders and hernias

- Psychosocial impact (school/work absence)

Prognosis

- Generally favourable with graded rehabilitation and self-management

- Poorer outcomes with severe deconditioning, high fear-avoidance, persistent dysautonomia, significant mood/sleep disorders

Early, team-based rehab (physio + psychology when needed) outperforms passive care; deprescribe ineffective analgesics.

References

- Malfait F, Francomano CA, Byers PH, et al. The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2017;175(1):8-26.

- Castori M, Tinkle B, Levy H, Grahame R, Malfait F, Hakim A. A framework for the classification of joint hypermobility and related conditions. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2017;175(1):148-157.

- Tinkle B, Castori M, Berglund B, et al. Hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (hEDS) and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders: clinical description and management. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:293-312.

- Simmonds JV, Keer R, Campbell F, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation in hypermobility-related disorders: consensus and practical guidance. Curr Treatm Options Rheumatol. 2021;7(4):1-16.

- Hakim AJ, Grahame R. A simple questionnaire to detect hypermobility: an adjunct to the Beighton score. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(3): 666-668.

- Celletti C, Camerota F, Castori M, et al. Orthostatic intolerance and autonomic dysregulation in hEDS/HSD. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2017;175(1):204-211.

- Roma M, Marden CL, De Wandele I, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome and Ehlers–Danlos hypermobility spectrum disorders: a narrative review. Auton Neurosci. 2018;215:1-8.

- Fikree A, Aziz Q, Grahame R. Gastrointestinal manifestations of joint hypermobility-related disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(9):1467-1476.

- Barton CJ, Bird ML, Pacey V, et al. Therapeutic exercise for people with generalised joint hypermobility: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;103(3):566-581.

Discussion