Overview

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is a chronic autoimmune neuromuscular disorder where antibodies target acetylcholine receptors (AChR) or MuSK proteins at the post-synaptic membrane, impairing neuromuscular transmission and causing muscle weakness

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is a rare autoimmune disorder marked by fluctuating muscle weakness that worsens with activity and improves with rest, commonly affecting the ocular (ptosis, diplopia), bulbar (dysphagia, dysarthria), and proximal limb muscles; severe cases may involve respiratory muscles, leading to myasthenic crisis. It is most prevalent in women under 40 and men over 60, with a strong association with thymic hyperplasia in about 70% of cases. Early diagnosis and treatment → such as pyridostigmine, immunosuppressants, and thymectomy → are crucial to prevent complications and improve outcomes.

Aetiology and Risk Factors

The specific aetiology of MG remains largely unclear, however some genotypes have been shown to increase the risk. These include human leukocyte antigen complex (HLA) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP’s). The presence of autoimmune diseases in family members is thought to also be a risk factor.1

The biggest associated factor for MG is a dysregulated thymus. MG is associated with thymic hyperplasia in 70% of pateints. This is because the thymus contains a small number of “myoid” cells, which are the only known cells outside of muscle to express AChR on their surface.2

[ MG is mainly associated with patients who have a dysregulated thymus, specifically thymic hyperplasia!].

Pathophysiology

MG has two possible mechanisms that target two different antigens:

- In MG associated with acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibodies, the immune system attacks these receptors, resulting in dysfunction and destruction of the neuromuscular junction at the post-synaptic membrane by blocking the binding of Ach to AChR. This pathologic mechanism is present in 80-90% of MG patients.3

- In MG associated with muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK), antibodies attack this protein which plays a role in anchoring AChR at the post-synaptic membrane. This is less common in patients with MG.4

Clinical Manifestations

The hallmark feature of MG is skeletal muscle weakness and corresponding muscle fatigue, which worsens with exercise and is relieved upon rest. Patients often present with complaints of specific muyscle weakness and not necessarily generlised muscle fatigue.

The muscle weakness can occur in ANY muscle, however more common thatn not it affects the ocular muscles first (in two thirds of patients) and bulbar muscle function in comparison to other groups (neck, limbs and respiratory muscles):

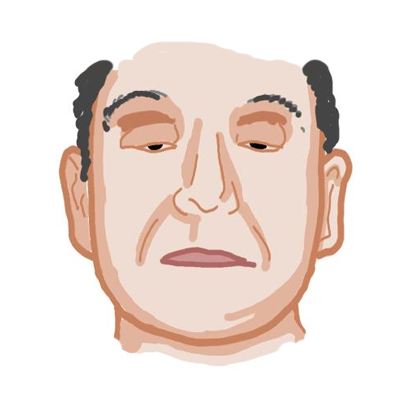

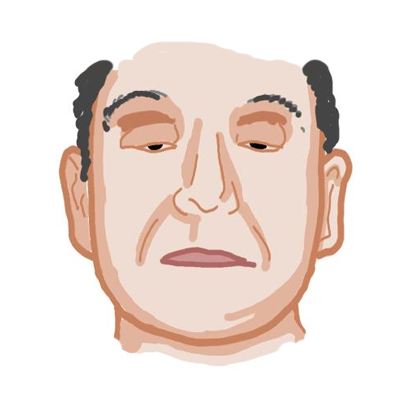

- Ocular function: Presents typically as ptosis (drooping of the eyelid) or diplopia (double vision)6

- Note: The “ice pack” test is a part of the neurological exam that is based on the principle that neuromuscular transmission improves at lower muscle temperatures, therefore improving ptosis in MG when the eyelids are cooled.

Figure 2: Ptosis of the left upper eyelid in MG7

- Bulbar function: Relates to oropharyngeal or facial muscle weakness and may present with dysphagia, dysarthria or the inability to make certain facial expressions.

- Limb function: Limb weakness is common in patients with generalised MG but doesn’t typically show upon first presentation. The pattern of limb weakness is commonly proximal, with arms > legs8

- Respiratory function: Patients typically develop respiratory muscle weakness later down the line in MG and is the most severe manifestation, leading to respiratory failure, also termed as “myasthenic crisis”.

This image series is only available to members

Diagnosis

MG is a clinical diagnosis which is supported by labs and other additional tests:9, 10, 11

- Best and first line– Serological testing: For most patients with features of MG, a supporting positive serology result is enough to diagnose MG. The antibodies testes for are:

- a. AChR antibodies: Found in up to 90% of patients and should be the INITIAL lab test performed to confirm the diagnosis.

- b. MuSK antibodies: This is the SECOND LINE antibody test and is done if patients do not have AChR antibodies. MuSK antibodies are only present in up to 10% of patients.

- Second line – Electrodiagnosic confirmation: This is done to confirm the diagnosis of MG when clinical features are ATYPICAL and initial serology yields negative or very low results.

- a. Involves nerve conduction testing with repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS), which involves repeated simulations of the motor nerve to the affected muscle and measuring the total sum of muscle action potentials. In normal muscles there is no change in the total sum, however in MG patients, there is a progressive decline in the total sum with the initial stimuli.

- Additional testing if the above yield negative results or if other diagnoses need investigation.

- a. Pharmacological testing – Edrophonium test: Edrophonium is a short-acting acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that increases ACH at the neuromuscular junction, leading to rapid, temporary improvement in muscle strength. In MG, this often results in noticeable improvement of ptosis.

- b. Imaging: CT can be done to detect thymoma or thymic hyperplasia.

Differential Diagnosis

- Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS): Muscle weakness that IMPROVES with exercise, separating it from MG. It is usually due underlying conditions such as small cell lung cancer.

- Botulism: Presents similarly to MG with ptosis, diplopia and muscle weakness, however systemic symptoms may also be present such as hypotension, bradycardia, diarrhoea – constipation.

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis: Can present with ocular symptoms and photophobia but is mainly accompanied by headaches.

Classification

Myasthenia gravis can be appointed one of five main classes that indicate its severity:12

- Class 1: Muscle weakness ONLY affects the ocular muscles

- Class 2: Muscle weakness is MILD and affects the ocular muscles as well as other muscles

- Class 3: Muscle weakness is MODERATE and affects the ocular muscles as well as other muscles

- Class 4: Muscle weakness is SEVERE and affects the ocular muscles as well as other muscles

- Class 5: Defined as myasthenic crisis, where the respiratory muscles are affected. This is the most severe stage.

Treatment

Management strategies for MG revolve around 4 main approaches:13

- Symptomatic treatment: Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (Pyridostigmine bromide) are the mainstay for symptomatic treatment as they increase levels of ACH at the neuromuscular junction and REDUCE muscle weakness.

- Immunosuppressive treatment: Used if symptomatic treatment is ineffective. Glucocorticoids (prednisone etc.) and azathioprine are FIRST LINE, followed by methotrexate, cyclosporine or tacrolimus.

- Immunoglobulin treatment: Intravenous immunoglobulins and plasmapeheresis is the treatment of choice for myasthenic crisis and is also recommended during the perioperative period to stabilise a patient before a procedure.

- Surgical treatment: A thymectomy is indicated for patients wit any evidence of thymoma or thymic hyperplasia.

Complications and Prognosis

The majority of patients with MG live normal lives and are minimally affected, with the rates of myasthenic crises happening in only about 4.5% of the population.

Complications for MG include:

- Myasthenic crisis: Respiratory distress as a result of respiratory muscle weakness. Often occurs secondary to infections or other stressors

- Medication associated reactions

- Aspiration pneumonia

Prognosis

Most patients lead near-normal lives with appropriate treatment. Myasthenic crisis occurs in ~4.5%, often triggered by infection or stress.

References

- Giraud M, Vandiedonck C, Garchon HJ. Genetic factors in autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1132:180–92.

- Hohlfeld R, Wekerle H. The role of the thymus in myasthenia gravis. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1994;4(4):373–86

- Yi JS, Guptill JT, Stathopoulos P, Nowak RJ, O’Connor KC. B cells in the pathophysiology of myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2018;57(2):172–84. doi:10.1002/mus.25973

- McConville J, Farrugia ME, Beeson D, Kishore U, Metcalfe R, Newsom-Davis J, et al. Detection and characterization of MuSK antibodies in seronegative myasthenia gravis. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(4):580–4. doi:10.1002/ana.20061

- Gomez F, Mehra A, Ensrud E, Diedrich D, Laudanski K. COVID-19: a modern trigger for Guillain-Barre syndrome, myasthenia gravis, and small fiber neuropathy. Front Neurosci. 2023;17:1198327. doi:10.3389/fnins.2023.1198327

- Kaminski HJ, Li Z, Richmonds C, Ruff RL, Kusner L. Susceptibility of ocular tissues to autoimmune diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;998:362–74. doi:10.1196/annals.1254.043

- Foroozan R, Sambursky R. Ocular myasthenia gravis and inflammatory bowel disease: a case report and literature review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003 Sep;87(9):1186–7.

- Werner P, Kiechl S, Löscher W, Poewe W, Willeit J. Distal myasthenia gravis: frequency and clinical course in a large prospective series. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;108(3):209–11. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.00136.x

- Vincent A, Newsom-Davis J. Acetylcholine receptor antibody as a diagnostic test for myasthenia gravis: results in 153 validated cases and 2967 diagnostic assays. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48(12):1246–52. doi:10.1136/jnnp.48.12.124

- Beloor Suresh A, Asuncion RMD. Myasthenia Gravis [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559331/

- Nicolle MW. Myasthenia gravis and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016;22(6, Muscle and Neuromuscular Junction Disorders):1978–2005. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000415

- Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. MGFA Clinical Classification. [Internet]. New York (NY): MGFA; [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://myasthenia.org/wp-content/uploads/Portals/0/MGFA%20Classification.pdf

- Beloor Suresh A, Asuncion RMD. Myasthenia Gravis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. [Updated 2023 Aug 8; cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559331/

Discussion