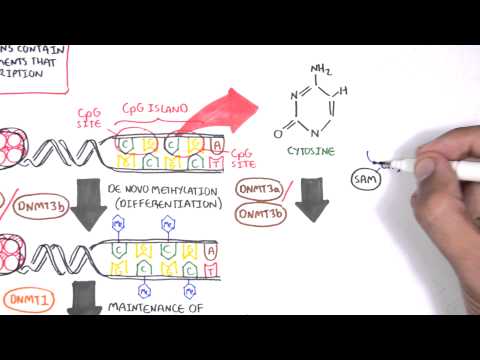

0:00 Hello, in this video we're going to talk about oncogenetics, the mechanism of 0:11 cancer from 0:12 a gene point of view. 0:14 In order to understand this, we have to learn again about the cell cycle. 0:19 So a normal cell can just be at rest. 0:23 This is at a quiescent phase, the G0 phase, the cell can then enter the cell 0:30 cycle. 0:31 The first phase of the cell cycle is known as the G1 phase, the growth phase. 0:37 This is where the cell's organelle duplicates. 0:40 So here you can see the mitochondria of the cell duplicated. 0:44 After the growth 1 phase is the S phase, also known as the synthesis phase, 0:49 this is when 0:49 the DNA duplicates. 0:53 The S phase, there is a G2 phase, where the cell essentially grows again, the 0:59 growth phase, 1:01 and prepares itself for the M phase. 1:04 The M phase is also known as mitosis, where a cell, which is now ready, 1:10 essentially divides 1:12 into two identical daughter cells. 1:15 These new cells can then re-enter the cell cycle, or go back to the G0 phase. 1:23 Now the cell cycle is, as it looks, a continuous cycle. 1:28 However, things can go wrong throughout the cell cycle, and so it's important 1:32 to have 1:33 checkpoints to make sure that there are no problems along the way. 1:37 The first checkpoint is actually at the end of the G1 phase, called the G1 1:41 checkpoint. 1:42 This is to make sure that there's no problems in the DNA and in the cell itself 1:48 . 1:49 The second checkpoint is at the G2 checkpoint. 1:51 This is to make sure that the cell has no problems before it enters mitosis. 1:56 And then there's another checkpoint at the M phase as well. 1:59 The cell cycle is a continuous progression from G1, S, G2, and M. But what 2:04 actually drives 2:06 the cell through the cell cycle? 2:08 Well, when a cell enters the cell cycle, it will start making proteins, 2:13 allowing it to 2:13 go and progress through the cell cycle. 2:16 These proteins are your cyclins and your CDKs, which are the drivers of the 2:22 cell cycle. 2:23 So for example, a cell wants to enter the cell cycle. 2:27 The cell will start producing proteins, the CDK and cyclins. 2:31 In the early G1 phase, CDK4 and 6 are produced. 2:37 And when cyclin D binds onto this, it will cause a reaction to occur inside 2:42 that cell. 2:43 It will cause E2F to detach from the retinoplastoma protein. 2:47 When E2F is released, it acts like a transcription factor, allowing that 2:52 particular cell to progress 2:54 through to the S phase. 2:56 However, at the end of the G1 phase, there's also another CDK in cyclin, CDK2, 3:03 and cyclin 3:04 E. Once at the S phase, the cell will produce another CDK in cyclin, CDK1 and 2 3:09 , and even 3:10 cyclin A. And then the G2 phase, again, CDK1 and cyclin B. And these CDK in 3:18 cyclins, again, 3:19 will allow the cell to progress through the cell cycle. 3:22 So CDK in cyclins are the drivers of the cell cycle. 3:26 If you have two low amounts of CDK in cyclin, the cell doesn't really progress 3:30 through the 3:31 cell cycle. 3:33 But if you have too much cyclin in CDK, then you get these cells that 3:37 continuously enter 3:38 the cell cycle, and thus you get this uncontrolled growth of cells. 3:43 And this is one of the mechanisms of cancer. 3:46 So what can potentially cause an increase in CDK in cyclins within the cell? 3:52 So this is where genetic mutations come in, so the mechanism of cancer, genetic 3:58 mutations. 3:59 So let's just look at this normal cell and pull out its genetic material, which 4:04 is DNA. 4:05 DNA is a double-stranded helix made up of four types of nucleotides. 4:10 Now mutations can occur within the DNA, which will cause changes to that cell. 4:17 Some types of mutations include point mutations, a single change in a nucle 4:22 otide. 4:22 Another is what's called DNA amplification. 4:25 When a certain gene gets amplified so many times, it could be a bad gene, for 4:30 example. 4:31 Then there's another one called chromosomal rearrangement, where the chromosome 4:35 basically 4:36 attached to one another where it shouldn't. 4:39 And another one is called epigenetic modifications, such as methylation and 4:45 acetylation of genes. 4:47 And this can essentially silence certain genes, and even cause genes to become 4:53 more active. 4:54 And so you can imagine with these mutations, a normal cell can become a cancer 4:59 cell. 5:00 And so when the cell enters a cell cycle, you get an uncontrolled cell growth. 5:05 It bypasses all the checkpoints, you get uncontrolled cell growth. 5:10 And these uncontrolled cell growth is essentially caused by two main changes 5:15 that occurs in 5:16 cancer cell. 5:17 These are one activation of oncogenes, such as the rast gene and your NYC gene. 5:26 The other change is the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes, such as in 5:32 activation of 5:33 P53, APC, and RACCA1 and 2. 5:39 So the mechanism of uncontrolled cell growth, as we discussed, the point 5:43 mutations, the 5:44 gene amplification, the chromosomal rearrangements, the epigenetic 5:48 modifications, these mechanisms 5:51 of uncontrolled cell growth essentially causes two main things in the cancer 5:57 cell. 5:57 These are activation of oncogenes and inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. 6:03 So now let's look at each of these in a bit more detail, beginning by looking 6:08 at oncogenes 6:10 first. 6:12 So let's begin by looking at oncogene activation, looking at the RAS and MYC 6:18 gene as an example. 6:19 So let's look at this cell here that's about to enter the cell cycle at the G1 6:25 phase. 6:25 Now normally, normally our cell contains DNA and normally our cells contain a 6:32 gene called 6:32 the RAS gene. 6:34 Now the RAS gene makes the RAS protein, which basically is an intracellular 6:38 protein that 6:39 sits below the plasma membrane. 6:41 Next to it is a receptor, the growth factor receptor. 6:46 Now obviously normally, when a cell enters a cell cycle, there is a growth 6:52 factor which 6:52 stimulates the growth factor receptor. 6:56 When the growth factor is stimulated, it will actually activate the RAS protein 7:01 . 7:01 Once the RAS protein is activated, it will cause a cascade of intracellular 7:05 phosphorylation 7:06 of other proteins, which will essentially at the end activate a transcription 7:13 factor. 7:13 Once this transcription factor is activated, it will essentially go to the DNA 7:19 and read 7:20 the genes to make proteins, to make proteins for cell growth, particularly to 7:26 make proteins 7:28 to allow the cell to go from the G1 phase to the S phase. 7:32 And these proteins are the CDK encyclins we talked about. 7:36 So you can imagine what would happen if you have a mutation in the RAS gene. 7:41 When you have a mutation in the RAS gene, you are making actually RAS proteins 7:45 which 7:45 are already activated. 7:47 And so you get always this cascade of phosphorylation events, and you always 7:51 get the activation 7:52 of these transcription factors. 7:54 And so you are over producing at the end these proteins for cell growth, such 7:59 as the cyclins 8:00 and CDKs. 8:03 Now the MIC gene is another one. 8:06 The MIC gene normally makes proteins in our body. 8:11 These proteins are important for cell growth, cell survival, and also cell 8:16 activity. 8:17 And so when you have a mutation of the MIC gene, the cell becomes more cancer 8:21 ous. 8:22 You get more cell growth, more cell activity, and more cell survival. 8:26 And so activation of these oncogenes, activation of the RAS gene and the MIC 8:32 gene, for example, 8:33 will allow a cell to bypass the checkpoints of the cell cycle, and will allow 8:39 the cell 8:40 to have an uncontrolled cell growth. 8:43 Now normally the cell has a mechanism to stop any abnormal cells from 8:48 progressing to the 8:49 cell cycle. 8:51 This is where tumor suppressor genes come in. 8:53 So for example, let's just say the cell gets held up at the G2 phase, because 8:59 it has an 8:59 abnormal DNA. 9:01 It has a damaged DNA. 9:03 This cell that was stopped with the damaged DNA will not progress through the 9:07 cell cycle 9:07 because it is abnormal, it has a damaged DNA. 9:11 So now let's talk about how this happened. 9:13 Let's talk about tumor suppressor genes normally, focusing on P53. 9:18 So let's zoom into this cell. 9:20 The cell contains damaged DNA. 9:22 When there's damaged DNA, the cell produces P53 proteins, which can act like a 9:28 transcription 9:29 factor. 9:33 It will read the DNA and will actually make proteins. 9:35 It will make proteins for cell arrest, such as P21. 9:43 What does P21 do? 9:45 Well P21 is a protein that causes cell arrest. 9:49 It actually inhibits the CDK and cyclins, and thus it inhibits the drivers of 9:55 the cell 9:55 cycle, so the cell cycle will not progress. 9:59 P53 will also make proteins important for cell repair, and so hopefully when 10:06 the cell 10:06 is arrested, the cell can repair itself. 10:10 It can repair the DNA. 10:13 The P53 protein will also make proteins important for apoptosis. 10:17 If the cell cannot repair itself, it has to die, because we don't want any 10:21 abnormal cells. 10:24 So you can imagine now if you have inactivation of tumor suppressor genes, such 10:28 as inactivation 10:29 of P53. 10:34 When you have inactivation of P53, you are not making proteins for cell arrest. 10:38 You're not making proteins for cell repair. 10:42 You're not making proteins for apoptosis, and so you have this cell that enters 10:45 the cell 10:46 cycle and can bypass the checkpoint and continuously grow and proliferate. 10:51 And so in summary, the genetic changes that occur in cancer are the in 10:57 activation of the 10:58 tumor suppressor genes and the activation of the oncogenes. 11:04 And so you have the cell that enters the cell cycle and can bypass the 11:07 checkpoint and continuously 11:09 grow and proliferate. 11:10 I hope this video was helpful. 11:12 Thanks for watching. 11:21 [BLANK_AUDIO]