“To lose confidence in one’s body is to lose confidence in oneself.”

― Simone de Beauvoir

“Every woman knows that, regardless of all her other achievements, she is a failure if she is not beautiful.”

– Germaine Greer

Overview

Overview Eating disorders have traditionally been classified into two well-established categories. They are anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Eating disorders are rare in the general population, they are relatively common in teenagers and young women. The disorder is associated with substantial physiological disruption and symptom overlap with other psychiatric illnesses, especially mood and anxiety disorders. Although 90% of patients with an eating disorder are female, the incidence of diagnosed eating disorders in males appears to be increasing.

| Definition Eating Disorder Anorexia Nervosa Anorexia Nervosa – Restrictive Type: During the current episode of anorexia nervosa, the person has not regularly engaged in binge eating or purging behaviour (self induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas) Anorexia Nervosa Binge eating/purging type: during the current episode of anorexia nervosa, the person has regularly engaged in binge eating or purging behaviour (ie. self induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas) Bulimia Nervosa |

Psychiatric History

Mnemonic SCOFF to assess risk of eating disorder

- S – Do you make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full?

- C – Do you worry you have lost Control over how much you eat?

- O – Have you recently lost more than One stone (6.35 kg) in a 3-month period?

- F – Do you believe yourself to be Fat when others say you are too thin?

- F – Would you say Food dominates your life?

Risk Factors

- Female

- Adolescence

- Obsessive traits

- Media exposure

- Identical twin affected

- Family dysfunction

Comorbidity is common. Mood, anxiety (especially social phobia) and substance use disorders occur most frequently.

Signs and Symptoms

Clinical Presentation Anorexia Nervosa generally presents during adolescence or young adulthood and is characterized by a relentless and often intensifying pursuit of thinness, leading to behaviour that contributes to the maintenance of a low body weight.

- Changed attitude to food and cooking

- Avoiding meals

- Slow eating/picking at food

- Eating in secret

- Cooking for family not for self

- Eating low calorie foods

- Changing food choices (eg. vegetarian or vegan diet)

- Medical problems

- Weight fluctuations with possible denial of diet or deliberate weight loss

- Fractures from minimal force

- Menstrual irregularities – due to hypothalamic dysfunction, low fat stores, malnutrition

- Gastrointestinal problems (eg. bloating, constipation, generalised abdominal pain, changing bowel habit)

- Hypoglycaemia – may present as ‘dizzy spells’

- Behavioural and psychological presentations

- Raiding the fridge

- Social phobia with regard to eating

- Excessive work or training

- Low mood or mood instability

- Poor concentration

- Self diagnosis

- New food intolerance (eg. lactose intolerance)

- Suddenly developing ‘allergies’ to foods

| Side note Most patients present late in the course of illness. Up to 50% of adults with anorexia nervosa may never seek treatment and people with bulimia nervosa present on average a decade or more after onset. |

Clinical Examination

- Arrhythmia – Electrolyte disorders, heart failure, prolonged corrected QT interval

- Bradycardia Heart muscle wasting, associated with arrhythmias and sudden death

- Brittle hair and nails – due to Malnutrition

- Oedema

- Hyperkeratosis – Malnutrition, vitamin and mineral deficiencies

- Hypotension – Malnutrition, dehydration

- Hypothermia – Thermoregulatory dysfunction, hypoglycemia, reduced fat tissue

- Lanugo (fine, white hairs on the body) – response to fat loss and hypothermia

- Marked weight loss – Self starvation, low caloric intake

Course of Anorexia Nervosa

- Generally begins with weight loss from dieting, although weight loss due to medical illness may also be an initiating event.

- Initial weight loss leads to a pattern of escalating interest in weight loss and commitment to restrictive eating.

- Engage in excessive exercise as well as “purging” (a repetitive pattern of vomiting or abuse of laxatives or diuretics).

- Commonly report body-image distortion, believing that they are less thin than they appear to others or that they have been or will be excessively fat or large at normal weights.

Differential Diagnosis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Coeliac disease

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hyperthyroidism

- Central nervous system tumours, lymphoma, leukaemia

- Depression

- Obsessive compulsive disorder

- Anxiety disorder

Investigations and Diagnosis

In most cases, patients with an eating disorder will have normal laboratory results. However, it is important to assess electrolyte, hormonal imbalance as these change in eating disorders:

- FBC

- EUC

- MCP

- Random blood glucose

- FSH

- LH

- Oestrodial

Anorexia Nervosa Diagnosis

- Restriction of energy intake relative to requirements

- significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health.

- Intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat, or persistent behavior that interferes with weight gain, even though at a significantly low weight.

- Disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low body weight.

Management

The management of anorexia nervosa remains a major challenge for two reasons:

- No treatment has clear empiric support.

- Patients with the disorder tend to underuse treatment, either not seeking care themselves or not receiving appropriate referrals for weight-restoration interventions

Multidisciplinary team

- Dietician

- Psychologist/psychiatrist

- Family physician

- Mental health services

Management

- Family-based therapy (FBT), also known as the Maudsley Method, for people under 18 years

- Cognitive behavioural therapy

Acute treatment Hospital treatment should be considered if there is immediate danger to life secondary to physical deterioration; suicide risk; no adequate outpatient treatment available or the patient has failed to progress despite appropriate outpatient treatment.

| Admission criteria for eating disorders |

| Bradycardia (resting heart rate <50 bpm) |

| Orthostatic hypotention (>10 mmHg systolic) |

| Hypothermia (temp. <35.5oC) |

| Arrhythmia |

| Severe electrolyte disturbances, eg. hypokalaemia (K <3.0 mmol/L) |

| Acute dehydration from refusal of all food and fluids |

| Remember Involving families in the treatment process is essential for better outcomes; family based therapy has the strongest evidence base for treatment in this age group. |

Complication and Prognosis

Complications due to Re-feeding

- Re-feeding syndrome – Due to rapid nutrition replacements, fluid shifts can occur, potentiated by electrolyte abnormalitiesOedema

- Oedema

- Hypophosphataemia

- Hypomagnesamia

- Acute thiamine deficiency

Complications of anorexia

- Anaemia

- Primary Amenorrhoea

- Female infertility

- Osteopaenia

- Osteoporosis

- Growth retardation

- Bone fractures

- Slowed GI motility

- Acute and Chronic renal failure

Prognosis

- 45% recover completely

- 40% improve

- 20% develop chronic eating disorder

- 5% die (mortality higher if younger)

Bulimia Nervosa

Overview Bulimia nervosa involves the uncontrolled eating of an abnormally large amount of food in a short period, followed by compensatory behaviors, such as self-induced vomiting, laxative abuse, or excessive exercise

| Side note Patients with eating disorders often engage in excessive physical activity despite bad weather, illness, or injury. |

Signs of Bulimia Nervosa

- Dental/gum disease – Recurrent vomiting washes mouth with acid and stomach enzymes; mineral deficiencies

- Oedema – Laxative abuse, hypoproteinuria, electrolyte imbalances

- Parotid gland enlargement – Gastric acid and enzymes from vomiting cause parotid inflammation

- Scars or calluses on fingers or hands – Self-induced vomiting

- Weight fluctuations, not underweight

Management

- Self help books

- Dietician

- Psychologist – CBT

Prognosis In 2-10 years:

- 50% improve

- 20% show no change

Consent and Confidentiality and the Adolescent

Consent – VICKS

- Voluntary

- Informed

- Capacity

- Specific

Consent and the Adolescent

- >18 deemed adults

- >16yo – can give consent themselves (and parents cannot give consent on their behalf) and should be treated like adults.

- <14yo – parent would have to give consent, not adolescent.

- Assent VICKS

- Must be for childs best interest (court can over rule)

- 14-16yo – Gray area (Gillicks competence or mature minor)

There are some treatments or procedures (e.g., sterilization) for which parents cannot give consent, irrespective of the child’s age.

Confidentiality and the Adolescent

- Health problems which can occur in adolescence include mental disorders, unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections and substance misuse.

- For these sensitive issues, prevention or early intervention is desirable.

- However, adolescents’ concerns about confidentiality can be a barrier to their accessing health services

- Understandably, parents have an interest in knowing about their children’s health problems

- Children may not feel the same way

- Assess adolescent maturity

- Capacity to understand

- Gillick competence (Mature Minor)

- Encourage adolescent to talk to parent/s

Adolescents have the legal right to confidentiality unless:

- Not a mature minor

- The adolescent consents to disclosure.

- The adolescent is at risk of harm or of harming others

- They are at serious risk of self-harm

- They are at risk of or the victim of physical or emotional abuse

- They are at imminent risk of harming others

- Some disorders such as psychosis, may need special consideration about the risk of harm and therefore the need to inform others

- Legal requirement for disclosure

- Court proceedings

- Notifiable diseases

- Blood testing for alcohol or other drugs

- It is necessary for the adolescent’s well-being

- Urgent communication in an emergency

- Communication between members of a treating health care team

Prescribing to a minor The following must be met:

- Mature minor (gillicks competence)

- Consent obtained (VICS)

- Medication is for the patients best interest

- Doctor weighs the risks and benefits – medication is safe, appropriate and lawful

- Doctor documents the medication and dose

Suicide

Overview Suicide is widespread across many age groups, and is associated with mental illness such as depression and other factors. Suicide is likely to be under-reported as deaths from suicide may be difficult to distinguish from accidental or intentional injury. It is important to note that suicide attempts are up to 20 times more frequent than completed suicide.

- In 2000, one million people worldwide died from suicide (1 death every 40 seconds)

- Suicide rates have increased by 60% worldwide in the last 45 years

- Suicide is one of the three leading causes of death among those aged 15-44 in both genders

| Side note Suicide among medical practitioners is higher than other professional groups in many industrialised countries, especially among female doctors. Risk factors for suicide are the same as the general population, however there is greater knowledge about how succeed and the availability of methods which may contribute to relatively high suicide rates. |

| Definition Mental illness: A term referring to a group of conditions that significant affect how a person feels, thinks, behaves, and interacts. Mentally disordered person: A person (whether or not suffering from mental illness) whose behavior for the time being is so irrational as to justify a conclusion on reasonable grounds that temporary care, treatment, or control of the person is necessary |

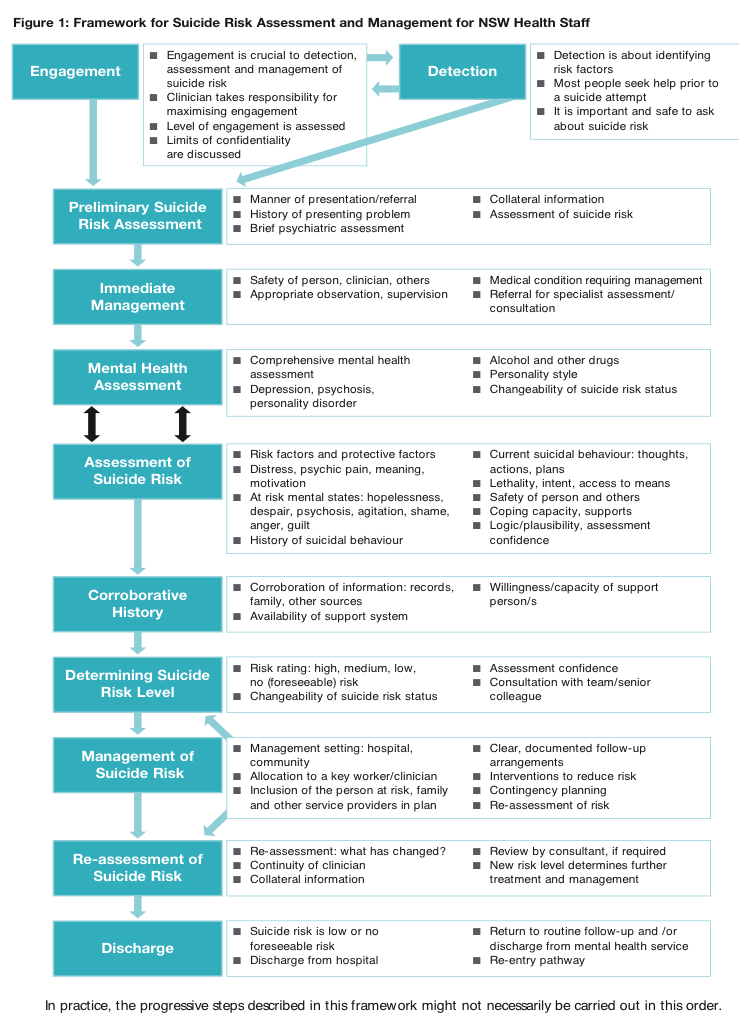

Suicide risk assessment – Important to complete when dealing with all patients who have mental health problems. The aim is to evaluate the likelihood of suicide attempt in the period of assessment.

Self-harm assessment (brief)

- Motivations

- At-risk mental states – Hopelessness, despair, psychosis, agitation, shame, anger, guilt

- Current suicidal behaviour – Thoughts, actions, plan

- Lethality, intent and access to means – Degree of determination, established plans, anticipated rescue, belief that they would die, finalization of personal business

- History of suicidal behavior or self harmSafety of person and others (homicidal intent)

-

- Coping capacity and supports

- Corroborative or collateral history – Records, family, other sources

- Potential triggers of presenting complaint

- Recent stressors

- Change in medications

- Change in social situations including relationships

- Major life events

| RISK FACTORS AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS OF SUICIDE | ||

| Groups at Risk of suicide | Risk Factors | Protective Factors |

| History of attempt or self-harm | Male | Strong perceived social supports |

| History of mental illness | Between 25-44yo | Family cohesion |

| History of sexual or physical abuse/neglect | Older people | Peer group affiliation |

| Domestic violence | Living in rural areas | Good coping and problem solving skills |

| Substance abuse | Recent break-up | Positive values and beliefs |

| Physical illness | Sexual identity conflicts | Ability to seek and access help |

| Refugees, immigrants | Financial difficulties | |

| Homeless | Impending legal prosecutions | |

| Lack of support | ||

Involuntary treatment

- Involuntary treatment must be reasonable, necessary, justified and proportionate

- The Doctor must have:

- Personally examinE or observed the person immediately or shortly before completing the certificate

- Formed the opinion that the person is either mentally ill or mentally disordered

- Is satisfied that involuntary admission and detention is necessary (and there are no less restrictive care reasonably available that is safe and effective)

- Is not the primary carer or a near relative of the person

Discharge following admission

- Patients who have been at risk of suicide need close follow-up when discharged

Discussion