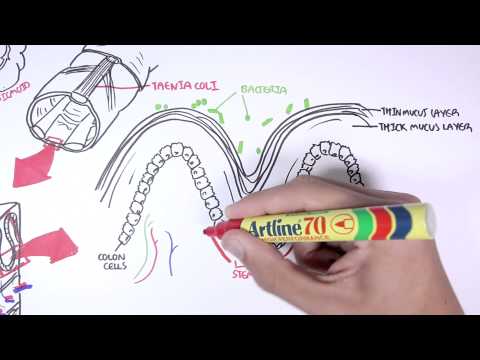

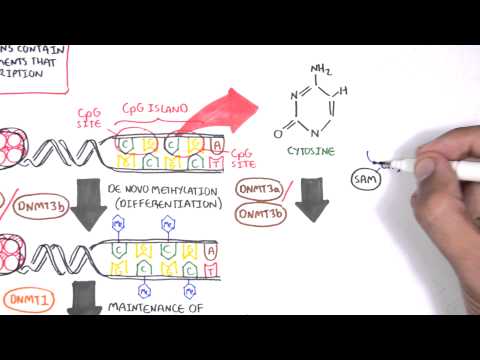

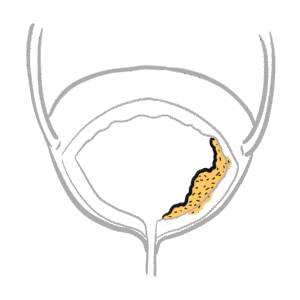

0:00 In this video we'll talk about carcinogenesis of colon cancer, and we'll 0:05 look at it at a molecular level and see what kind of mutations occur along the 0:09 DNA that will result in cancer of the colon. So we begin by looking at normal 0:16 colon cells that have their blood supply. Here where the crypts are, stem cells 0:22 will migrate up, giving rise to new colon cells. If we look into the genetic 0:29 material of one of these stem cells, their genetic material is DNA, which is 0:36 found in chromosomes. The DNA is all tangled up around histones. If we remove 0:42 the histones, here we can see the DNA. In a normal colon cell, there is a 0:52 balance 0:52 between what's called histone acetylation and histone methylation. 0:57 Histone acetylation means that there is a better access for transcription 1:02 factors to the DNA. Histone methylation means that there is decreased access 1:10 for 1:10 transcription factors to the DNA. So there is repression. Therefore, if there 1:17 is a 1:18 lot of methylation, certain genes may not be activated. So looking at the 1:27 histones here, we have a balance between histone methylation, ME, and histone 1:33 acetylation AC. Now an important enzyme to know is HDAC, which is histone 1:40 dacetylase. This enzyme essentially removes an acetyl group from the histone. 1:47 So 1:48 here the enzyme is removing the acetyl group from this histone. And HDAC is an 1:57 important enzyme in decreasing access for transcription factors essentially. 2:05 Now 2:06 along the DNA, there are regions called promoter regions and non-promoter 2:12 regions. Promoter regions are regions in the DNA that initiate transcription of 2:19 particular genes, meaning the synthesis of RNA. Therefore, non-promoter regions 2:26 are regions that contain no functional genes. In a normal cell, colon cell, 2:36 there is approximately 70 to 80% methylation in non-promoter regions. But 2:45 around the promoter regions, genes are usually un-methylated. And this is so 2:53 there is better access for transcription factors to activate genes. And we will 3:01 see the changes that occur in methylation as cancer develops. Now in 80% of 3:10 cases of 3:10 colon carcinogenesis, there is an adenomatous polyposischoline gene mutation, 3:15 or APC gene mutation. The APC gene is essentially a tumor suppressor gene, 3:23 because normally it encodes for proteins involved in cell adhesion and 3:29 transcription. This APC mutation can result in one of these stem cells to 3:37 become a potentially cancerous. And so as the abnormal cell, the potential 3:46 cancer 3:46 cell moves up, it will begin dividing and dividing, creating a polyp, which is 3:54 usually a small benign growth. However, with more mutations, such as in 50 to 4:03 60 4:03 percent of colon cancer cases, there is activation of the KRAS oncogene, as 4:09 well 4:10 as more mutations of other tumor suppressor genes. Now the KRAS gene 4:16 normally controls cellular division. However, a mutation of the KRAS gene 4:23 results in a KRAS oncogene and thus cell proliferation. The cells will begin to 4:34 proliferate. This will create an adenoma, which is a larger benign growth. 4:41 During 4:42 this time, as the cells keep dividing, there needs to be more blood supply in 4:48 order to feed the growing tissue. So angiogenesis, which is formation and 4:54 maturation of blood vessels, occur. It should be noted that from when the 5:01 potential cancer cell, the abnormal cells develop, there can be a mismatch a 5:08 repair gene inactivation, as well as hypermethylation occurring on the DNA. 5:15 The mismatch repair gene normally repairs mutations that occur on the 5:22 genes, in the genes. Hypermethylation silences genes. Both mismatch repair 5:30 gene inactivation and hypermethylation can result in mutation rates that are 5:37 a hundred time fold greater than mutation rates that occur in normal 5:42 cells, which is a lot of mutations. A mutation in the TP53 gene tends to occur 5:52 later in colon carcinogenesis. This mutation will cause resistance of 5:59 cancer cells to apoptosis. So more cells will divide and less will die. This 6:10 will 6:10 cause a massive growth, which will cave in and keep growing, resulting in 6:17 carcinoma, which is a malignant growth. Now that we're at this stage, let us 6:26 look 6:26 at the genetic material of this cancer cell. So here we have the chromosome 6:32 again, the 6:33 histone fibers and the histone, and then the DNA. The DNA, which has, remember, 6:39 the 6:40 promoter and non-promoter regions. In cancer cells, there is a 6:46 disbalance between histone, acetylation, and histone methylation. So we see 6:55 more 6:55 methylated histones. Remember, methylation decreases access to transcription 7:02 factors. One reason why we see more methylation is because of HDAC, the 7:11 enzyme, which appeared to be more active in colon cancer cells. So here HDAC is 7:21 removing all the acetyl groups on histones, resulting in more methylated 7:28 histones. In colon cancer cells, we also see changes in DNA methylation. In 7:38 promoter regions, for example, there is usually hypermethylation, particularly 7:44 in tumor suppressor genes and DNA repair genes. This results in some of the 7:50 mutations we talked about earlier. And in non-promoter region, there tends to 7:57 be 7:57 fewer methylation. So again, there is hypermethylation on promoter regions, 8:04 which contributes to gene silencing and genomic instability, and it will affect 8:11 apoptosis, DNA repair, and cell cycle control. And there tends to be a decrease 8:19 in methylation on non-promoter regions, which essentially don't do anything. 8:25 I hope you enjoyed this video on colon cancer carcinogenesis. Thank you for 8:30 watching.