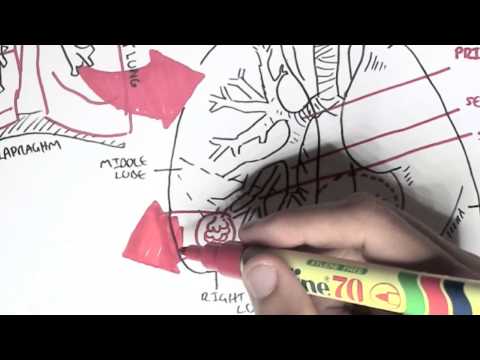

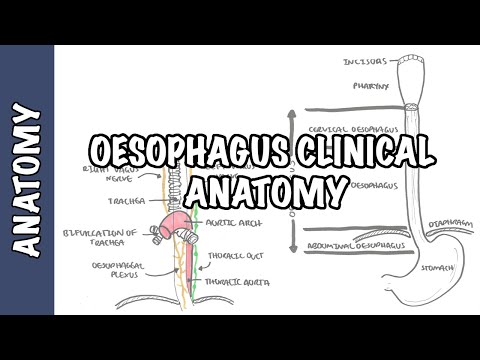

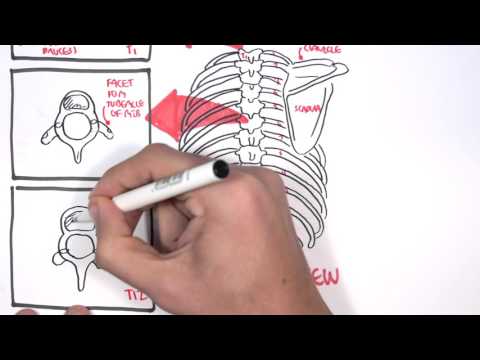

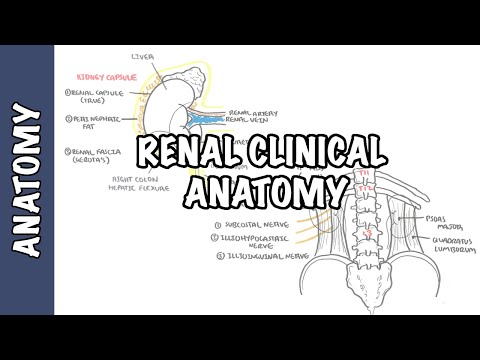

0:00 Hello, in this video, we're going to talk about the Lung Chlora. 0:13 This is a clinical anatomy video. 0:17 Let's begin by reviewing the respiratory tract briefly, starting from the laryn 0:23 x here, 0:24 which goes down to the trachea, trachea bifurcates into the primary bronchi, 0:30 which then enters the right lung and the left lung. 0:35 Behind the respiratory tract is the esophagus, which then leads to the stomach, 0:42 below the diaphragm. 0:44 Each lung is enveloped or enclosed by a sac, which consists of a continuous, 0:50 serious membrane. This is the pleura, and the pleura will form the pleura 0:58 cavity. 0:58 So here you have the right lung pleura, and you have the left lung pleura. 1:05 You can think of the lung pleura, like the pericardium of the heart. 1:11 Like the pericardium, it's a sac, where the lungs sit. 1:19 Here is the diaphragm, which is an important muscle for respiration, 1:22 together with the intercostal muscles and the seratis. 1:27 The heart sits here in the mediastinum. 1:29 The liver is in the right upper quadrant, below the diaphragm. 1:34 Let us now look at the pleura and see its relationship to the bones. 1:40 Medial and anterior, you will find here the manubrium, the sternum, and the x 1:47 iphoid process. 1:49 The clavicle is on top and attaches to the manubrium. 1:53 Here is the axilla, your armpit area. 1:57 And here you have the ribs, which protect your lungs and heart, as shown. 2:02 You have 12 ribs numbered here in red. 2:08 Some important anatomical landmarks, if we draw a straight line in the middle 2:12 of the clavicle, 2:13 we can call this the mid-clavicular line. 2:16 And here is your mid-axillary line, where the axilla is. 2:20 You draw a straight line down, where your armpit is essentially on the side of 2:24 your body. 2:25 These are landmarks which are good to know, because you can tell where roughly 2:29 the lung margins 2:30 and the pleural margins are. 2:32 Remember that each lung is enclosed in a pleural sac. 2:36 The pleural margins we are talking about here is the outermost pleura membrane, 2:42 called the parietal pleura. 2:44 And we'll talk about this more a bit later. 2:47 Anyway, as you can see, at the mid-clavicular point, the lungs should end at 2:55 about the sixth rib. 2:58 In this diagram, it shows the seventh rib. 3:02 But let's just say it's the sixth rib. 3:04 The pleural margin is always too above this, so it ends as shown at the eighth 3:12 rib. 3:13 Looking at the mid-axillary point, you can see the lung margins ends at the 3:17 eighth rib. 3:18 And the pleural margin, which is too above this, ends at the tenth rib. 3:24 Let's now focus more on the lung pleura, and why it is a sac, which holds the 3:37 lungs, 3:37 and why there are two pleural membranes, even though it's actually one 3:41 continuous membrane. 3:43 Here is the part of the respiratory tract and the lungs. 3:47 Here are the ribs. 3:48 Here is ribs eight and ribs ten. 3:51 Remember, the lung margins at the mid-axillary is about the eighth rib. 3:58 Before introducing the pleura membrane and the pleural cavity, 4:03 remember the root of the high limb here, because it is here where the 4:08 continuous sheet of the lung pleura 4:11 changes from what's called the parietal pleura to what's called the visceral 4:18 pleura. 4:18 The parietal pleura in blue extends to the roots of the lung, the high limb, 4:24 you can say. 4:25 But remember, the pleural membrane is a continuous sheet, and it continues, 4:30 and then it continues and envelopes the lung. 4:33 This in orange now is known as the visceral pleura, which essentially adheres 4:40 to the lungs. 4:41 So again, at the root of the high limb, you have the parietal pleura, which 4:46 goes and attaches to the thoracic wall. 4:48 And at the root of the high limb is when it changes into the visceral pleura, 4:53 which envelopes the lungs. 4:55 So you can say that the visceral pleura and the parietal pleura meet at the 5:01 root of the high limb. 5:02 And thus, the pleura itself is a continuous, serious membrane, serious sheet. 5:08 And this continuous membrane or sheet is more like a sac where the lungs 5:13 actually sit. 5:14 Now, because it is a sac in between the parietal and visceral pleura, you have 5:19 the pleural cavity or the pleural space. 5:23 In the pleural cavity, you have pleural fluid. 5:26 The pleural fluid flows through the pleural cavity. 5:30 The pleural reflection is essentially a line where the pleura itself, the ple 5:36 ural membrane, changes direction. 5:39 To complete this diagram, really important, the parietal pleura in blue covers 5:45 the superior surface of the diaphragm 5:47 and moves with the diaphragm during respiration. 5:52 Here is the mediastinum where the heart sits. 5:55 Now, let's cut a cross section of this area of the thorax to better understand 6:00 the pleural membranes and the pleural reflections. 6:04 Here is the posterior part of the thorax. 6:07 You can see the spine, the vertebrae. 6:11 Here are your primary bronchi, which enters your lungs on the left and on the 6:15 right. 6:16 Remember, you have in blue your parietal pleura, which attaches to the thoracic 6:21 wall. 6:22 Surrounding the lung is the visceral pleura, which is the continuation of the 6:27 parietal pleura. 6:28 The changes in name and direction described is known as the pleural reflection. 6:36 In between the parietal and visceral pleura is the pleural cavity, which 6:40 contains the pleural fluid. 6:43 In front of the vertebrae, and behind the trachea is where the esophagus goes 6:50 down. 6:50 Next to the esophagus, more so on the left side, is the descending aorta. 6:56 The mediastinum can be divided into several compartments, as you know, one of 7:01 which is the posterior compartment, 7:03 where we can find the esophagus, the descending aorta, and then you have the 7:07 middle compartment of the mediastinum, 7:09 where we can find the heart. 7:11 And then you have the anterior compartment, which is the sternum. 7:15 Now let us draw a posterior view of the body, and let us now look at more body 7:21 landmarks, 7:21 so we can again outline the lung margins and the lung pleura from the back. 7:28 Looking at the back of the person here, you can find the scapula, the vertebral 7:32 spine. 7:33 In front of the scapula and vertebrae, you have the right and left lung, and 7:39 you also have the pleural membrane. 7:41 Coming off the thoracic vertebrae, you have the ribs, your ribs. 7:46 Here is ribs 10 to 12. 7:50 Again, if we draw a line down the middle of the scapula, you can call this now 7:55 the mid-scapula line. 7:57 The lung margins, as you can see, finishes at about the 10th rib in the mid-sc 8:03 apula line. 8:04 And the pleura finishes at about two above this, which is ribs number 12. 8:11 Again, the mid-exillary line is the imaginary line running through where your 8:15 axillae is, your armpit, basically on your side. 8:25 Let us take a closer look at this area here down the bottom, and look at it in 8:31 a bit more detail and the structures. 8:33 Here is your visceral pleura, which covers the lungs. 8:35 Here is the parietal pleura, which is a continuation of the visceral pleura, 8:39 and attaches to the thoracic wall. 8:42 And here is a space in between, which is called the pleural space, or the ple 8:48 ural cavity. 8:49 Now, the parietal pleura, in blue, as I mentioned, attaches to the thoracic 8:53 wall. 8:53 And here, the thoracic wall are your ribs. 8:56 In between the ribs are your intercostal muscles, which hold the ribs in place 9:01 and also assists in respiration. 9:03 From the inner layer of the intercostal muscles is the innermost intercostals, 9:10 then after that is the internal intercostals, and then your external intercost 9:14 als. 9:15 This area I'm drawing here can also be called the left costo diaphragmatic 9:20 recess. On a chest x-ray, this area is called the left costo phrenic angle. 9:26 Now, the left costo phrenic angle is very useful to look at on a chest x-ray, 9:31 because clinically, if there is blunting, or if the edge is filled, sort of, 9:36 this can signify pleural effusion. 9:39 The diaphragm attaches superiorly to the parietal pleural layer. 9:46 Plural fluid builds the pleural space, and pleural fluid comes from the par 9:52 ietal pleural circulation, which is the main source. 9:56 It also comes from the visceral pleural circulation from the lungs, and also 10:04 partly from the peritoneal cavity via small holes in the diaphragm. 10:11 Now, the pleural membrane in summary has many functions, but two main ones. 10:16 Firstly, you can imagine, because it attaches to the lungs and the thoracic 10:21 wall, it actually allows for changes in lung shape during respiration. 10:26 And secondly, the pleural prevents the lungs from collapsing, maintaining 10:34 positive, trans pulmonary pressure. 10:39 Let's zoom into this area here, where the parietal and visceral pleural are in 10:44 close proximity, and learn a bit more about the physiology of the pleural 10:49 itself. 10:50 So, again, here in orange is the visceral pleural, and in blue is the parietal 10:55 pleural. 10:56 In between the visceral and parietal pleural is the pleural cavity. 11:07 The visceral and parietal pleural is made up of mesothelial cells. 11:13 Below the visceral and parietal pleural is the basement membrane. 11:19 The space below the visceral pleural is a visceral space, which is also 11:24 basically the lungs, which contain the alveoli and the pulmonary capillaries, 11:29 ready for gas exchange. 11:31 The parietal space is also the thoracic wall. You have systemic capillaries in 11:38 this area. 11:38 You also have lymph vessels here called the parietal lymph vessels, which drain 11:45 the fluid from the pleural space. 11:48 Interestingly, as discussed, the source of the pleural fluid is mainly from the 11:54 parietal pleural, from its systemic circulation. 11:58 There is also some fluid produced from the visceral pleural as well. 12:02 Ultimately, the fluid circulating through the pleural cavity will drain into 12:08 the parietal lymphatics mainly, 12:11 and the parietal lymphatics is able to absorb 20 times more fluid than is 12:17 normally formed, 12:18 which is kind of important, especially if there's too much parietal fluid being 12:23 produced. 12:24 The substance that are found in the parietal fluid are also things that are 12:29 produced by the mesothelial cells, 12:31 which include things such as glycoproteins, TGF-beta, and nitric oxide. 12:38 Now, let's look at some clinical anatomy of the lung chlora, beginning with ple 12:43 uritis, which is inflammation of the parietal pleural, mainly due to viral 12:48 infections. 12:49 Clinical signs include shortness of breaths and pleuritic chest pain, which is 12:53 characterized by essentially pain when breathing in, 12:56 and also, pleuritis has a characteristic pleuritic rub, which can be heard 13:02 during expiration and inspiration. 13:04 Sounds like creaking or grating sounds, something like this. 13:19 Again, the main cause are viruses, but autoimmune conditions can also cause ple 13:29 uritis. 13:30 The next clinical anatomy condition for the lung chlora is pleural effusion, 13:36 which is accumulation of fluid in the pleural space, 13:39 usually as a result of inflammation of the pleural. 13:43 Standing up means gravity will push the fluid down. The area where the fluid is 13:49 means that there is decrease in breath sounds if you try to listen to it there. 13:54 And also, there will be dullness on percussion because it's just solid, all 13:59 fluids. 13:59 There will be also decrease in lung expansion. 14:02 Here's an example of a chest x-ray with someone who has left-sided pleural eff 14:08 usion. 14:08 Here is the meniscosine, and as you can see, all this colored here is fluid 14:15 within the pleural cavity. 14:17 Usually small pleural effusions resolve alone, but if there's so much and if 14:24 you want to diagnose the cause of the pleural effusion, 14:26 you can do what's called a cardiocentesis or pleural tap. 14:31 The procedure is essentially where you aspirate excess pleural fluid, and this 14:37 is both therapeutic, but also the fluid can be analyzed to see what is in it. 14:42 This can help the doctor help them identify a potential cause of the pleural 14:48 effusion, either heart failure or cancer or autoimmune, for example. 14:54 The next clinical anatomy condition is a pneumothorax, which is essentially 15:01 where you have accumulation of air in the pleural space. 15:05 Numo as an air thorax is in the thorax. 15:08 Now, there's two main mechanisms of how people get pneumothorax. 15:13 These are spontaneous pneumothorax and open pneumothorax. 15:19 Spontaneous pneumothorax is usually a result of a ruptured bullet seen in lung 15:26 conditions such as COPD. 15:28 This rupture of bullet causes air essentially to leak into the pleural space, 15:34 and so when there's so much air that occupies the space, 15:37 it will actually push against the lungs causing partial collapsing of the lung. 15:43 An open pneumothorax is usually due to an external trauma, which causes air to 15:49 leak into the pleural cavity from the outside, and this also causes the lung to 15:54 collapse again. 15:55 When you percuss, it will actually be hyper resonant, because there is air 16:00 within the cavity. 16:01 This means that when you oscillate the area, there will be usually reduced 16:06 breath sounds or even no breath sounds. 16:08 As you can see, here is an example of a chest x-ray of someone who has a left- 16:12 sided pneumothorax. 16:13 As you can see, this line denotes the lung, and it's being pressed by air that 16:21 's entering the pleural space. 16:25 There's something called pneumothorax, and then there's something called 16:28 tension pneumothorax, which is a life-threatening condition. 16:31 It is really where there's over-accumulation of air in the pleural space, 16:36 usually as a result of a valve mechanism. 16:38 So, it's usually from an external trauma causing an opening, such as maybe like 16:44 a cut or a wound. 16:45 Now, the opening somehow works as a valve, in which when you breathe in, 16:51 inspire, air will come in and it will increase the pleural pressure. 16:56 And when you expire during expiration, however, the air can't leave the pleural 17:04 space, because the hole closes up like a valve. 17:07 And so you can imagine with each inspiration, pressure will build up in the ple 17:13 ural cavity. 17:13 This causes the lungs to collapse even more, and also the large increase in 17:19 pressure will stop pushing other structures around. 17:22 For example, it will cause tracheal deviation to the opposite side of where the 17:28 tension pneumothorax is. 17:29 It will also push against the heart, causing decreased cardiac output, and 17:34 hence, hypotension. 17:35 The compression of the heart can also mean there is an obstruction of the heart 17:40 -filling system, causing a characteristic raised in JBP. 17:45 Here is an example of a chest x-ray of someone who has a left-sided tension 17:51 pneumothorax. 17:52 As you can see, all this area here is air, not within the lungs, but within the 17:59 pleural space. 18:00 And it is collapsing, it totally collapsed the lung, and also starts to push 18:05 against the other structure, pushing all structures to the right. 18:09 You can see tracheal deviation, you can see compression of the heart. 18:13 This is life-threatening. 18:15 And because tension pneumothorax is a life-threatening condition, what needs to 18:19 be done is an emergency needle decompression. 18:22 Classic approach is second intercostal space, midclavicular, with a needle 18:28 allowing air to essentially exit from the pleural space.