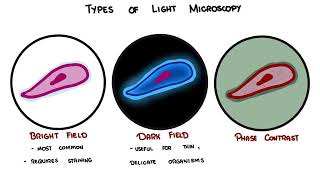

0:00 When you first look at bacteria under a normal light microscope without any 0:11 preparation, 0:12 you'd see almost nothing. 0:15 Microbes are incredibly small, most bacteria are only a few micrometers wide 0:19 and viruses 0:20 are even smaller and nearly transparent, blending into the background. 0:26 This invisibility is what made the microbial world hidden for so long. 0:31 It wasn't until the invention of the microscope in the 17th century that Ant 0:36 oine Van Lewenholk 0:37 first described anima-cules revealing a vast new dimension of life. 0:44 Today, microbiology depends on microscopy, not just to magnify these organisms, 0:50 but also 0:51 to resolve fine details that distinguish one microbe from another. 0:57 Staining techniques add contrast and colour, turning invisible specks into 1:03 identifiable 1:04 structures and in many cases, providing immediate diagnostic clues that guide 1:09 treatment. 1:10 In this way, microscopy is more than just a laboratory tool. 1:15 It is the lens through which the microbial world and its impact on human health 1:19 comes 1:19 into focus. 1:21 So how does microscopes work? 1:25 A microscope takes really very small things and makes them visible by magn 1:30 ifying them and 1:31 increasing their resolution. 1:35 Magnification makes objects appear larger, resolution determines how clearly 1:39 you can 1:40 see two points as separate. 1:43 With normal light, the best resolution is about 0.2 micrometers, that's enough 1:48 to see bacteria, 1:50 but viruses are far too small. 1:53 For those, we need electron microscopes. 2:01 So let's briefly talk about the types of microscopes. 2:05 So a light microscope is a microscopy technique that uses visible light and 2:12 glass lenses to 2:13 produce magnified images of specimens. 2:18 How it works is that visible light passes through the specimen and is focused 2:23 by glass 2:24 lenses. 2:25 The maximum resolution is about 0.2 micrometers, which is sufficient to 2:29 visualize most bacteria 2:31 and larger organisms such as yeast. 2:35 Hydrogen is up to 1,000 times using oil immersion objectives. 2:40 It is really best used for assessing overall shape and size of cells, 2:46 arrangement of a 2:47 bacteria, whether it's cluster or in clumps or in chains, and also staining 2:53 patterns, 2:54 whether it is, you know, gram-positive or gram-negative bacteria, for example. 2:59 So this image is an example of a light microscopy. 3:04 It shows how different biological samples look when viewed under a microscope 3:09 at increasing 3:10 levels of magnification. 3:13 The top row shows a plant root tip and the bottom row shows a human blood. 3:18 At low magnification, the samples appear as general shapes or blurry areas, 3:22 making it 3:22 hard to see individual cells. 3:26 As the magnification increases, more detail becomes visible. 3:29 In the plant root, the tightly packed cells become clear and are arranged in an 3:33 orderly 3:34 brick-like pattern, while in the blood sample, down the bottom, individual red 3:38 blood cells 3:39 begin to stand out with the occasional white blood cells appearing darker. 3:44 At the highest magnifications, you can clearly see individual cells and their 3:49 internal features, 3:51 such as nuclei in plant cells and the distinct shapes of the red and white 3:55 blood cells. 4:00 So there are a few types of light microscopy. 4:04 These are some general ones. 4:06 You have bright field, which is really the most common type of light microscopy 4:11 . 4:11 Here, light passes directly through the specimen, usually require staining, 4:16 because bacteria 4:18 here are transparent. 4:20 You have dark field, a special condenser blocks direct light, so only scattered 4:20 light reaches 4:29 the lens. 4:30 The result is a bright specimen against a dark background, very useful for thin 4:35 , delicate 4:35 organisms, such as trepanoma pallidum syphilis. 4:40 There is another type of light microscopy, which is called the phase contrast, 4:43 which 4:44 enhances differences in refraction index between cell structures and 4:48 surroundings. 4:49 This makes internal details of living, unstained cells more visible, often used 4:55 for protozoa, 4:56 fungi or live bacterial cultures. 5:01 This image shows bacteria viewed using bright field light microscopy after a 5:06 gram stain. 5:07 The purple, round bacteria are gram-positive cocchi, often seen in clusters, 5:11 while the 5:12 pink are the rod-shaped bacteria and are gram-negative bacilli. 5:18 The scale bar, 10 micrometers, shows that these organisms are very small, and 5:25 only visible 5:26 at high magnification under a light microscope. 5:31 This image shows Borrelia, a spirochete bacterium that is particularly well 5:38 suited to dark field 5:40 microscopy, because it's extremely thin and transparent, making it difficult to 5:44 visualize 5:45 with standard bright field methods. 5:48 In dark field microscopy, as I mentioned, Borrelia scatters light along its 5:53 spiral body, causing 5:54 it to appear as a bright wavy filament against a dark background, and this 5:59 allows observation 6:00 of live, unstained organisms, and makes its characteristic shape and mortality 6:05 clearly 6:06 visible for identification. 6:09 This image shows cells viewed using a phase contrast microscopy, again enhances 6:14 the natural 6:15 differences in the cell density, allowing unstained living cells to be seen 6:20 clearly. 6:21 In the left panel, you have a bright field microscopy. 6:25 The cells are difficult to distinguish from the background, while in the right, 6:28 phase 6:28 contrast converts subtle differences within the cells into visible slight and 6:33 dark areas, 6:34 making these outlines and internal structures more easier to see. 6:40 This technique, again, is commonly used to observe live cells in culture 6:44 without killing 6:45 or staining them. 6:47 Light microscopy is really the entry point. 6:50 It's simple, it's widely used, and enough for basic bacterial morphology, but 6:56 it has 6:57 resolution limits. 7:00 Then you have this thing called the fluorescence microscopy. 7:08 This microscopy technique is where samples are stained with fluorescent dyes 7:16 called fluorophores 7:18 that really specifically bind to the cells, the microbes, or molecules of 7:24 interest. 7:25 How it works, the sample is illuminated with UV or blue light, which excites 7:33 this dye, 7:34 this fluorophores. 7:36 These fluorophores then emit light at a longer wavelength, visible light, 7:41 causing the labeled 7:43 structures to glow against a dark background. 7:47 In terms of magnification and resolution, it's similar to conventional light 7:52 microscopy, 7:53 but with much higher specificity, because only fluorescently labeled structures 7:58 are 7:59 visible, so you can clearly see things. 8:03 It's best used for detecting specific microbes, identifying specific cellular 8:09 components or 8:09 proteins, and it helps visualizing targets using fluorescent stains or antibody 8:17 labels. 8:18 In terms of clinical uses, it can be used for direct detection of mycobacterium 8:23 tuberculosis 8:24 in sputum using fluorescent dyes, rapid diagnosis of infections using 8:30 fluorescent antibody tests. 8:33 This fluorescent microscopy image shows standard eukaryotic cells, stained to 8:39 highlight different 8:41 internal structures. 8:43 The blue region are the cell nuclei, the green filaments represent the cytos 8:48 keleton of the 8:49 cell, typically microtubules, and the red are another type of filament, the act 8:55 in filament. 8:56 The black background indicates non-fluorescent areas, allowing the labeled 9:01 cellular components 9:03 to stand out clearly and reveal the organization and architecture of the cells, 9:08 and this is 9:08 what makes fluorescent microscopy very useful. 9:13 medicine doesn't give higher resolution than light microscopy, but it adds 9:17 specific targeting. 9:19 It's like turning microbes into neon signs that say, "here I am." 9:28 Finally electron microscopy. 9:31 This type of microscopy technique allows us to visualize things very, very 9:38 small, such 9:39 as viruses. 9:41 This microscopy technique is where you use electron beams instead of light to 9:47 image specimens. 9:49 How it works is that electrons are fired at the sample, at the specimen. 9:54 Because electrons have a much shorter wavelength than visible light, they can 9:58 resolve structures 9:59 that are far smaller than those seen with light microscopy. 10:04 And so it has extremely high resolution down to nanometers, with magnification 10:10 up to one 10:11 million times the size. 10:15 So it's really best used for detecting viruses, detailed bacterial structures, 10:21 cellular infrastructure 10:23 such as membranes, cell organelles. 10:27 There are two main types of electron microscopy, the transmission and scanning 10:32 electron microscopy. 10:34 One electron microscopy is where electrons pass through an ultra-thin section 10:38 of the 10:38 specimen and it produces detailed 2D images of internal structures, organelles, 10:43 viral particles, 10:45 flagella, cross sections. 10:47 This is an example of a transmission electron microscopy. 10:53 This is a virus. 10:55 You can see the particles revealing the small size and surface spikes in high 11:03 detail. 11:04 Scanning electron microscopy uses electrons that bounce off the surface of the 11:09 specimen. 11:10 It produces dramatic 3D images showing external structures like pill-eye, 11:16 surface texture, 11:17 or viral coats. 11:20 Universal microscopy is not used for routine diagnosis because it's too 11:24 expensive and 11:25 complex but is essential for research and detailed studies. 11:32 This picture is schistosoma, a parasite. 11:36 This image is taken using a scanning electron microscopy, highlighting this 11:43 parasite's detailed 11:44 three-dimensional structure surface as well as the texture. 11:51 So in summary, when you think of microscopy in layers, you have the light 11:54 microscopy which 11:55 is basic overview of bacteria and fungi. 11:59 You use this for gram-staining, for example. 12:02 Then you have the fluorescent microscopy which adds specificity. 12:06 It highlights particular microbes or structures using fluorescent dyes. 12:12 And then you have electron microscopy where it allows you to zoom into the nan 12:17 oscale revealing 12:18 the fine details of viruses, organelles, and surface. 12:21 It's not used to diagnose but it's more for research-based and understanding 12:26 structures 12:26 of different types of organelles. 12:29 Together these tools allow us to see the microbial world from the big picture 12:34 down to the tiniest 12:36 molecular machines. 12:42 the material. 12:43 The material is very important. 12:44 It's very important to see the material. 12:45 It's very important to see the material. 12:46 It's very important to see the material. 12:47 It's very important to see the material.