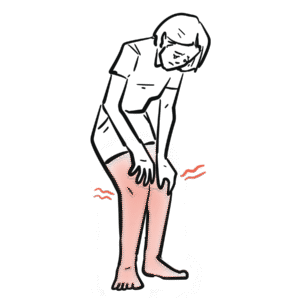

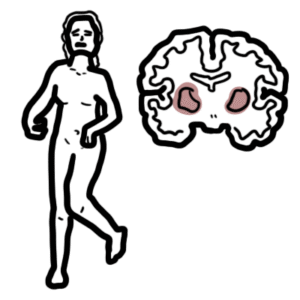

0:00 Epilepsy is a disease characterized by seizures. 0:09 Epilepsy, there are different types. 0:12 There are seizures that are well localized in the brain or that spread out 0:18 throughout 0:18 the whole brain. 0:19 In this video, we're only going to focus on the pharmacology of epilepsy. 0:25 So here I'm drawing the brain and the brain is made up of cells known as 0:30 neurons. 0:30 In epilepsy, you have episodic high frequency discharge of impulses by a group 0:34 of neurons 0:35 in the brain. 0:36 It can be in one part of the brain, so localized. 0:40 This will create what's known as a partial seizure or it can start local and 0:45 then spread 0:46 throughout the brain or throughout part of the brain and this is known as 0:50 generalized 0:51 seizure. 0:55 Before we go into the pharmacology of epilepsy, I think it's important to watch 1:01 a video on 1:03 how the neurons send signals to one another and have a video on that which I'll 1:08 provide 1:08 the link. 1:10 So again, epilepsy is characterized by seizures and it's where the neurons are 1:16 excited. 1:17 They just send all these impulses all the time. 1:21 So therefore, drugs to treat epilepsy can be divided into three types. 1:27 One, drugs that modulate voltage gated ion channels responsible for the 1:33 propagation of 1:33 the impulse. 1:34 Two, drugs that enhance basically synaptic inhibition, so stopping the impulses 1:41 . 1:41 And or three, drugs that stop or inhibit synaptic excitement. 1:49 So drugs that modulate voltage gated ion channels are drugs that target the 1:53 sodium and calcium 1:55 channels and these and they will inhibit these channels. 1:58 Drugs that enhance synaptic inhibition will cause increase in GABA activity, 2:04 which is 2:04 the inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS. 2:09 And then drugs that want to inhibit synaptic excitement will essentially 2:14 decrease glutamate 2:15 activity. 2:18 So again, to recap, in the central nervous system, you have two main neurotrans 2:24 mitters 2:24 that sort of counteract one another. 2:28 These are glutamate which are excitatory neurotransmitters and then you have 2:33 GABA which are inhibitory 2:35 neurotransmitters. 2:37 So this cell here, let's just say, is a glutamate glutaminergic neuron and they 2:43 will excite 2:44 the brain and they will send impulses and stuff like that. 2:48 And then of course, it will stimulate this post-synaptic neuron and this 2:54 happens, it 2:56 will result if it hits a threshold, it will result in a seizure. 3:00 And then you have this other neuron here in blue, which is inhibitory neuron 3:05 and these 3:05 inhibitory neurons release GABA. 3:07 GABA, again, is an inhibitory neurotransmitter. 3:11 And again, this neuron that releases glutamate is excitatory neuron. 3:19 So let's zoom in here where all these synapses are occurring and then learn a 3:23 bit more about 3:24 the physiology and then the pharmacology. 3:27 So here I'm drawing the glutaminergic neuron, the terminal bulb, and then here 3:30 we have the 3:31 post-synaptic neuron and then the blue here is the GABA-nergic neuron. 3:36 So when an action potential comes down, again, it essentially causes an influx 3:42 of sodium via 3:43 the voltage-gated sodium channels. 3:46 And then once it hits the terminal, this will cause the voltage calcium 3:50 channels to open 3:51 up resulting in calcium to come in and this will then lead to depolarization, 3:57 more positive 3:58 resulting in the vesicles in the terminal bulb to release glutamate in this 4:03 case. 4:04 It will bind onto receptors or channels in the post-synaptic neuron. 4:12 In this case, the glutamate neurotransmitters are binding onto the AMPA and NM 4:18 DA channels 4:19 resulting in the influx of sodium and calcium from outside, which will then 4:24 lead to depolarization, 4:26 reaching a threshold, which will result in an action potential. 4:29 So this is creating impulses, it's stimulating the neurons in the area. 4:36 And if this happens like a lot or consecutively, this will result in what's 4:43 known as a seizure. 4:46 So I hope that part of the story made sense and how that's exciting. 4:51 The neurons are exciting each other. 4:53 And then here in blue we have the GABA-nergic neuron with GABA in the terminal 4:57 bulb. 4:58 GABA is actually made from glutamate. 5:00 But anyway, this neuron can release GABA, right? 5:03 And the GABA can then bind onto its own receptors on the post-synaptic neuron 5:08 here, which are, 5:09 in this case, GABA-A receptors. 5:11 When GABA binds onto this receptor, it will actually cause an influx of 5:16 chloride ions, 5:17 which are negatively charged, and so it sort of counteracts the depolarization. 5:22 So it inhibits this process from happening. 5:25 Once GABA finishes its job, it gets taken back up to this terminal bulb, and 5:32 then it gets 5:32 converted to SSA through GABA transaminase. 5:38 So as you can see, we have a glutamate neuron on neurotransmitters, which are 5:45 exciting the 5:46 cells, and then you have GABA-nergic neurons, which releases GABA, and GABA are 5:50 the ones 5:51 that inhibit sort of suppress neuronal activity. 5:55 So this is regulated normally, but again in epilepsy, you have more excitement. 6:04 So now let's talk about the pharmacology, the drugs used to treat epilepsy. 6:09 Let's begin with the drugs that modulate voltage-gated ion channels. 6:13 And these drugs include carbazepine. 6:18 Side effects here in the side face include water retention, sedation, ataxia, 6:23 and mental 6:24 disturbances. 6:25 Finotone is another drug, and side effects include confusion, gum, hyperplasia, 6:31 skin 6:31 rash, anemia, and it's also teratogenic, so it's not good for pregnancy. 6:35 You have etho-suxamide, side effects include nausea and anorexia, and finally 6:40 in this group, 6:41 we have lomotrygene. 6:45 Then you have the other class of anti-apletics that want to stimulate GABA 6:50 activity, and these 6:51 drugs include benzodiazepines, V-gabertrin, and Tia-gabine. 7:00 I hope I pronounced those right. 7:03 So if we were to draw those drugs up in respect to this diagram, we have carb 7:08 amazepine, finotone, 7:10 and lomotrygene, which will inhibit the sodium voltage channels here, so thus 7:15 inhibiting 7:16 depolarization. 7:17 And then we have lomotrygene and etho-suxamide, which will inhibit the calcium 7:22 voltage gated 7:23 channels and also inhibiting depolarization, so stopping the glutamate activity 7:27 , essentially, 7:28 or excitment, or the neuronal excitment. 7:31 Then we have the benzodiazepine, which will stimulate essentially this receptor 7:37 activity, 7:38 this channel activity here, resulting in more GABA activity, resulting which 7:44 will inhibit 7:45 the depolarization, the excitment. 7:48 Tia-gabine will inhibit the reuptake of GABA, resulting in more GABA activity 7:53 in the synaptic 7:54 cleft. 7:56 Then you have the V-gabertrin, which will inhibit the GABA transaminase enzyme 8:04 here, which will 8:06 obviously result in more GABA being available in the synaptic cleft. 8:12 Then you have another anti-apletic drug, which I actually haven't introduced, 8:15 which 8:15 is sodium valproate, and it's quite a common drug for epilepsy, and it does 8:19 actually a 8:20 lot of these things, which I just mentioned, so it can target the voltage 8:25 channels and 8:25 it can stimulate the GABA activity. 8:28 I didn't group it into a particular class of anti-apletics, but it's important, 8:34 some 8:35 important things to realize is that in pregnancy, anti-apletics are not very 8:42 safe, so consideration, 8:44 so in pregnancy, we have teratogenic anti-apletic drugs, and these include phen 8:50 otone and lomatrogen 8:52 and valproate, however, it's been shown that lomatrogen is probably the most 8:58 safest out 8:59 of the lot, you can say, the best out of the lot for people who are pregnant. 9:05 So I hope you enjoyed this video on the pharmacology of epilepsy. 9:12 Thank you for watching. 9:14 �