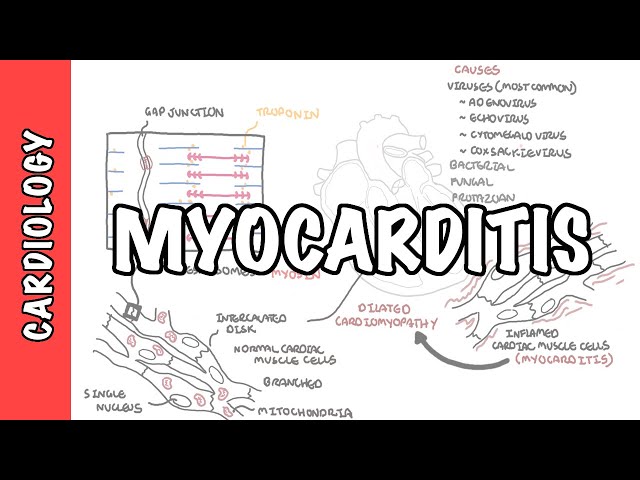

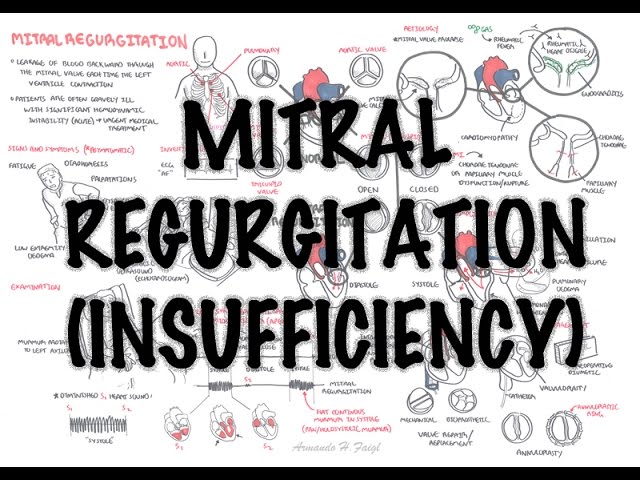

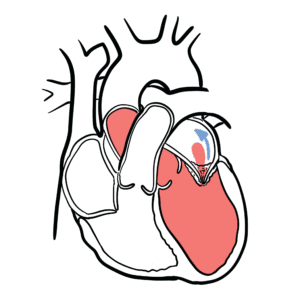

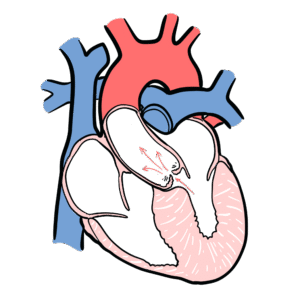

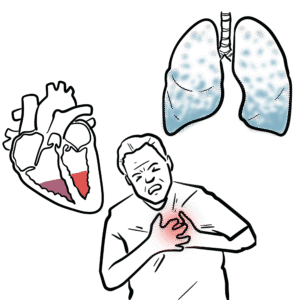

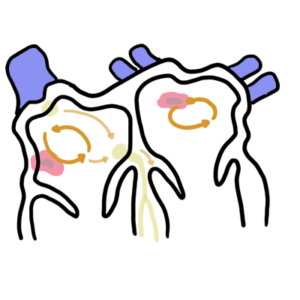

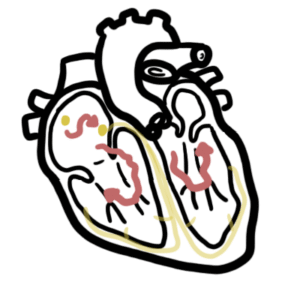

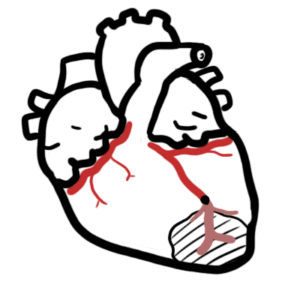

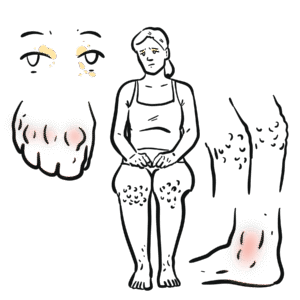

0:00 Cardiomyopathies are diseases of the heart muscle tissue. 0:16 Cardiomyopathies represent a heterogeneous group of diseases that often lead to 0:20 progressive 0:21 heart failure with significant morbidity and mortality. 0:25 When talking about cardiomyopathies, we often focus on ventricular heart 0:30 muscles, the bottom 0:31 two chambers of the heart. 0:32 Remember, the heart is a muscular pump, which pumps blood all over our body. 0:37 The cardiac muscle fibers, or cells, have a single nucleus, they are branched 0:42 and joined 0:43 to one another by interclated discs. 0:47 The interclated discs contain gap junctions. 0:50 The interclated discs and gap junctions form a syncydium of cardiac cells, 0:54 allowing the 0:55 heart to contract in a coordinated unified manner. 1:00 The dismosomes hold the fibers together when the heart contracts, and the 1:04 actual contractile 1:06 units of the cardiac muscles are the sarcomeres, which is made up of myosin and 1:10 actin filaments. 1:12 These two filaments slide past one another to cause a muscle contraction. 1:20 What happens is that the sarcomeres shortens during muscle contraction. 1:25 This is called systole. 1:27 Systole is when the ventricles contract and pumps blood out. 1:34 The sarcomeres lengthens, and this is where the cardiac muscle cells relax. 1:40 The relaxation process is termed diastole. 1:43 This is when the ventricles fill with blood preparing itself for another 1:48 contraction. 1:50 Because we're focusing on cardiac muscle cells and cardiomyopathies, we need to 1:53 learn 1:53 some fundamental physiology. 1:56 Remember there are three major determinants of myocardial performance, preload, 2:02 afterload 2:03 and contractility. 2:06 Focusing on the ventricular cardiac muscle cells, preload is the amount of 2:10 blood entering 2:10 the ventricles during diastole when the heart is relaxing. 2:15 An increase in preload means a stronger contraction, and this relationship is 2:20 the frank-styling 2:22 relationship, which can be depicted with this graph here, with di-endyostolic 2:27 volume on 2:28 the x-axis, how much blood enters the ventricles, versus stroke volume, which 2:34 is the volume 2:35 of blood ejected by the heart with each contraction. 2:44 To put it simply, as more blood enters the ventricles during diastole, this 2:49 increases 2:50 the length of the resting sarcomere, which builds up tension, kind of like a 2:57 spring. 2:58 Tension builds up as the ventricles fill with more blood and then bang, during 3:02 systole, 3:03 when the sarcomere shortens, it has all this tension and so it just increases 3:08 the contractile 3:09 force and therefore the stroke volume. 3:12 An increase in diastolic volume therefore increases stroke volume normally. 3:19 Preload is the other determinative cardiac muscle function, and this is the 3:23 force the 3:24 cardiomyocytes must overcome to pump blood out of our body. 3:29 Contractility of the heart muscle can be independent of preload, and for 3:33 example, the autonomic 3:34 nervous system ions can influence cardiac contractility. 3:42 To finish off this basic anatomy and physiology diagram, you know, troponin is 3:47 attached to 3:48 the structures here, and is important and involved in muscle contraction. 3:54 Cardiomyocytes also contain many mitochondria to produce large amounts of ATP, 3:59 which is needed 4:00 because the heart muscles always demand this energy, it's constantly pumping. 4:10 Dialated cardiomyopathy is the most common type of cardiomyopathy, and is 4:17 characterized 4:17 by dilation and impaired contraction of one or both ventricles. 4:24 Blood fills the ventricles during diastole. 4:29 During systole, there is impaired contraction. 4:33 The dilated ventricles are unable to eject all the blood out of the heart, 4:37 resulting in 4:38 reduced ejection fraction. 4:42 Plus the clinical features of dilated cardiomyopathy include symptoms of heart 4:48 failure, including 4:49 dysnia, orthopnea, and paroxysmonecturnal dysnia. 4:54 Clinically, there is the S3 gallop, the most specific sign for heart failure. 5:02 The S3 gallop, or the S3 sound, occurs just after S2 when the mitral valves 5:09 open, allowing 5:10 passive filling of the left ventricle. 5:13 The S3 sound is actually produced by the large amount of blood striking a very 5:18 compliant 5:19 left ventricle. 5:23 Dialated cardiomyopathy can be a primary condition as in genetics, or inherited 5:28 . 5:28 Or dilated cardiomyopathy can be secondary to something else, such as a viral 5:33 infection, 5:34 specifically COPSACI-B virus, substance abuse, such as alcohol and cocaine, 5:40 coronary artery 5:41 disease, however coronary artery disease causing cardiomyopathy is sometimes 5:47 called ischemic 5:48 cardiomyopathy, and then you also have valvular diseases causing what's called 5:54 valvular cardiomyopathy. 5:56 Other causes include arrhythmias. 6:01 As the ventricles dilate, they also can impact valvular function of the heart, 6:07 and results 6:08 in common complications such as mitral valve insufficiency, as well as tricusp 6:17 id insufficiency. 6:20 On echocardiogram, you can see a dilated ventricle. 6:25 This echocardiogram shows the left side of the heart. 6:30 Here you can see reduced ejection fraction from the systolic impairment, and 6:34 possibly 6:35 normal or reduced ventricular wall thickness. 6:39 You may see a component of mitral insufficiency. 6:44 Here is a real-time echocardiogram of a person with dilated cardiomyopathy. 6:48 Again, note the dilated left ventricle. 6:52 There is thinning of the left ventricular wall, and systolic function is 6:59 severely reduced. 7:01 Treatment for dilated cardiomyopathy is the same for heart failure therapy. 7:05 Fluid restriction, daily weights, diuretics, ACE inhibitor, beta blockers, and 7:14 spironolactone. 7:16 Here is a role for implantable cardiovirter defibrillators, or ICDs, and people 7:20 who have 7:21 fought heart failure and who are at risk of dying from arrhythmia. 7:27 The last line obviously is a heart transplant.