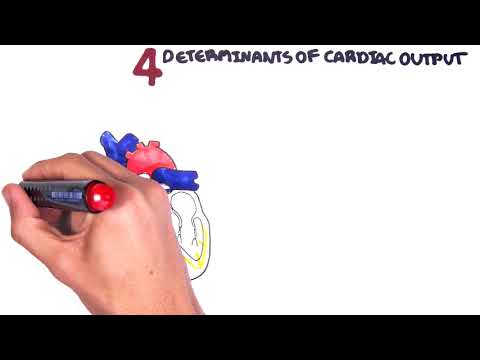

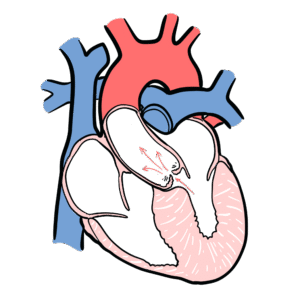

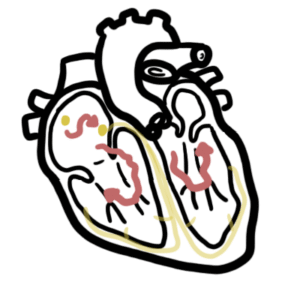

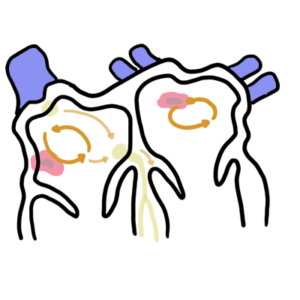

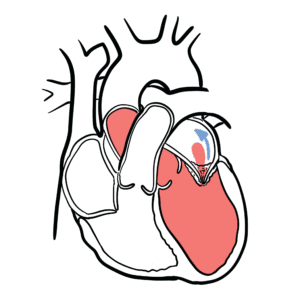

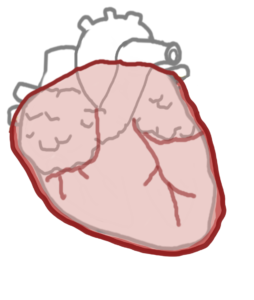

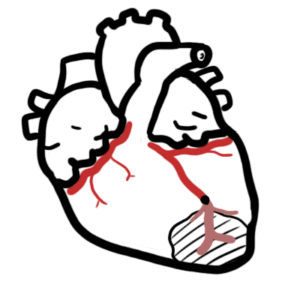

0:00 Armando Hausuirungan, Biology and Medicine videos, please make sure to 0:03 subscribe, join 0:04 the farming group for the latest videos, please visit Facebook at Armando Hausu 0:06 irungan, please 0:07 like. 0:08 Here you can also ask questions, answer questions, and post some interesting 0:10 things including 0:11 your hours. 0:12 You could also change the quality settings to the highest one for better 0:15 graphics. 0:16 Now here we have an open view of the heart. 0:20 We have the aorta and pulmonary artery leaving the heart and the superior vein 0:24 coming into 0:25 the heart. 0:26 Let's look at diastole, the time at which the heart fills with blood. 0:32 But when we say diastole or cystole, we usually are referred to the ventricles. 0:38 So here, diastole, we're looking at the filling of the ventricles with blood. 0:43 To just recapping, we have the right atrium and the left atrium filling the 0:48 right ventricle 0:49 and the left ventricle with blood. 0:52 So blood moves in. 0:54 When the ventricles are filling with blood during diastole, there can be no 0:58 blood coming 0:59 from the arteries, such as the aorta or the pulmonary artery, so only from the 1:06 atrium. 1:07 This filling mechanism, as well as the ejecting of blood out of the heart, is 1:13 because the 1:14 heart muscles contract, they depolarize. 1:17 However, muscles can only contract because of a special group of cells and 1:22 fibers that 1:23 coordinate the contraction process. 1:26 These cells are known as pacemaker cells, and the most important is a cyto-at 1:30 rial node 1:30 within the right atrium. 1:34 These pacemaker cells maintain the conduction system of the heart, and they 1:39 react automatically 1:40 without any nerves or whatever attaching to them, they're automatic. 1:45 But they also depolarize to send impulses. 1:48 So for example, the cyto-atrial node will depolarize and send impulses to the 1:54 right atrium and 1:55 the left atrium, causing it to contract, causing it to fill the ventricles with 2:01 blood. 2:01 Also, the impulse will travel to another important node, known as the atrial 2:06 venticular 2:07 node situated here. 2:09 The impulse coming into the atrial venticular node will pause for us for a 2:13 while to allow 2:14 ventricles to be fully filled up. 2:17 On the atrial venticular node, the impulse will travel essentially to the per 2:21 kingi fibers, 2:22 which will then cause the ventricles to contract to eject blood out of the 2:28 heart. 2:29 So it will cause the right ventricle and the left ventricle to contract to 2:32 eject blood 2:33 out of the heart. 2:34 This process of ejecting blood out of the heart through the pulmonary artery 2:40 and aorta 2:41 is known as cystol, where the ventricles contract eject blood out. 2:47 So we have diastole and cystol. 2:49 Diastole is filling, cystol is contracting, and during contraction there can be 2:56 no blood 2:56 coming from the atrium to the ventricle. 3:01 For a continue, please know that diastole and cystol can be for both atrium or 3:07 ventricle, 3:08 but they tend to be for ventricles. 3:11 Cystol basically means filling, and cystol means contraction, so atrium, diast 3:16 ole means 3:17 filling of blood to the atrium. 3:20 Anyway, from the beginning of the video, I mentioned that pacemaker cells can 3:25 only send 3:26 action potentials, send impulses, when they depolarize. 3:31 We can see how the pacemaker cells depolarize and send action potentials by 3:34 looking at a 3:35 membrane potential graph of the cynoatrial node, for example, the SA node. 3:43 So here we have the membrane potential on the y-axis and time on the x-axis. 3:48 We won't really look at time, we just won't understand what's happening. 3:52 So here is how the cynoatrial node sends out action potentials, sends out 3:58 impulses. 3:59 We can name each of these phases with numbers. 4:04 So four, zero, and three. 4:07 But you might think, where is phase one and phase two? 4:10 Well, it doesn't occur with pacemaker cells because one and two are 4:13 specifically for cardiac 4:14 muscle cells, and we'll soon see later why. 4:18 So for now, cynoatrial phases for action potential is four, zero, and three. 4:24 Let's begin with phase four. 4:26 Phase four begins at about negative 60 millivolts, and is when and is where we 4:32 have spontaneous 4:33 depolarization. 4:34 And as the name suggests, it's when the cynoatrial node spontaneously depolar 4:40 izes, becomes more 4:41 positive because of the influx of, because of the slow influx of sodium and 4:48 calcium ions 4:49 through, the calcium ions coming through T and also L-type channels. 4:56 Phase zero is depolarization. 4:58 When we have rapid influx of calcium ions through L-type calcium channels, 5:04 causing the 5:05 membrane potential to become more positive till about zero millivolts. 5:12 This is an action potential, and this is when it causes, this is when the cyno 5:16 atrial node 5:17 sends out the impulse, sends out the actual potential causing the atrial my 5:21 ocytes to depolarize, 5:23 as well as sending the impulse to the pacemaker cells to depolarize. 5:30 Then we have phase three, and this is where we have repolarization, when the 5:34 calcium ions 5:35 stop moving inside, and then we have the X flux, E flux of potassium ions, the 5:42 potassium 5:43 ions leaving the cell, causing the cell to become more negative, so it's rep 5:49 olarizing. 5:50 It will repolarize to about negative 60 millivolts, and then the calcium 5:55 channels will close. 5:56 And then the process continues, we have phase four again, spontaneous depolar 6:03 ization. 6:04 As you can see, this process is continuous, and it has to be, it has to be 6:09 continuous, 6:10 to provide blood to our body. 6:13 So these pacemaker cells, they work automatically with the same rhythm. 6:17 However, the pacemaker cells rate of depolarization can increase or decrease in 6:25 response to some 6:25 influence problem or condition. 6:30 For example, an increased rate of firing of sympathetic nerve fibers will cause 6:37 the rate 6:38 of spontaneous depolarization of the cynoatrial node to reach the threshold 6:43 more quickly, 6:45 causing an increase in heart rate. 6:48 So sympathetic activity will cause an increase in heart rate, and we see this 6:52 during exercise, 6:53 for example. 6:55 In contrast, we have the parasympathetic nerve innervation firing that will 6:59 cause the rate 7:00 of spontaneous depolarization to decrease, so slowing the heart rate, and we 7:06 see this 7:07 when we eat, for example. 7:12 So as you can see on this graph, the blue thing, the parasympathetic activity, 7:17 is causing this 7:19 spontaneous depolarization to be longer. 7:22 Okay, now we know that when these pacemaker cells depolarize, they will produce 7:27 an action 7:27 potential which will cause the muscles to contract. 7:31 This graph was specifically for the cynoatrial node action potential, however, 7:35 the atroventicular 7:36 node, AV node, and the perkinje fibers are somewhat similar, just not as strong 7:42 . 7:42 When these pacemaker cells coordinate the contraction of cardiac muscle cells, 7:47 the muscle 7:48 cells themselves have to depolarize in order to contract, if that makes sense. 7:53 So why don't we look at the muscle cells themselves, particularly the ventricle 7:58 muscle 7:59 cells, because they are the ones that eject blood out of the heart. 8:03 So here we have the graph again with the membrane potential on the Y and the 8:07 time on the X. 8:10 The changes in membrane potential of the ventricle muscle cells looks like this 8:15 . 8:16 So at rest, when nothing happens, it is at about 80 millivolts, but when it 8:21 contracts, 8:21 the muscle contract, they go up to about positive 20, someone like that, 8:27 positive 20 millivolts. 8:29 Now unlike this cynoatrial node with phases 0, 3, and 4, the ventricles have 8:35 phases 0, 8:37 1, 2, 3, 4, and this is because of the plateau phase, and we will talk about it 8:44 soon. 8:44 Now let's look at all these phases. 8:47 So phase 0, we have rapid depolarization, the membrane potential becoming more 8:51 positive 8:52 by the rapid influx of sodium ions. 8:55 This is the contraction of the ventricles. 8:59 Then at phase 1, we have a partial repolarization when the membrane potential 9:03 partially becomes 9:04 more negative. 9:05 This is when the sodium ions stop moving in and the potassium ions, we have 9:11 moving out. 9:12 So potassium efflux. 9:15 Then phase 2, we have the famous plateau phase. 9:18 When the potassium ions are actually still moving out, but we also have calcium 9:23 ions moving 9:24 in. 9:25 So it's like balancing each other out. 9:27 So we have potassium moving out and calcium moving in. 9:31 But after some time when we reach phase 3, the calcium as well as the sodium 9:36 ions, they 9:36 will stop moving in and we will only have potassium moving out. 9:40 And this is phase 3, it's called repolarization, becoming more negative. 9:46 Now phase 4 is when the ventricle muscles essentially rest and this phase is 9:51 also known 9:52 as the pace maker depolarization phase. 9:57 I want to explain why it's called pace maker depolarization, just try to think 10:01 about it. 10:03 But essentially during phase 4, we have all the ions moving back to the 10:09 original places. 10:11 So the sodium and the calcium are moving out and potassium moving back in where 10:15 they belong 10:16 or they originally came from. 10:18 And this is done through sodium-potassium ATP pumps, calcium sodium exchanges 10:25 and calcium 10:26 ATP pumps. 10:31 So from this graph, we can see that when the ventricles depolarize here, it's 10:37 when it 10:38 contracts. 10:39 And so we call this cystol because it's when the ventricles are ejecting the 10:44 blood as shown 10:45 by the high diagram on the left, the cystol diagram on the left. 10:49 And phase 4 is when the ventricles are filling with blood, so diastole. 10:56 Now important thing to know is that is the absolute refractory period, which is 11:00 the whole 11:01 duration of the action potential of the ventricle. 11:04 The absolute refractory period is when a second action potential cannot be 11:08 generated and so 11:09 we don't see a buildup of contractions, because otherwise we would have some 11:13 form of heart 11:14 attack. 11:17 Now knowing all this bit of information about cystol, diastol and when it 11:21 occurs and what 11:22 happens when it happens, let's look at an electrocardiogram. 11:32 Now you might see these at hospitals of the electrocardiograph when patients 11:35 are being 11:36 monitored, which is very important, especially in intensive care. 11:41 Now the normal cardiac cycle time is about 0.8 seconds. 11:44 You can correct me on this. 11:47 And we can letter these phases during a cycle starting from P in the electro 11:51 cardiogram. 11:53 It's easy to remember, so PQRST. 11:56 There's also a U, but that usually doesn't get brought up. 11:59 The only thing kind of how is to know what happens between these intervals. 12:05 Now this last P on the right should be after 0.8 seconds. 12:09 But I drew it there to make a point. 12:12 Now you know when the heart makes a sound when it beats. 12:15 Well it occurs at the tip of R and T. And we can notice and visually see these 12:22 hot sounds 12:23 through a phonocardiogram. 12:26 That's what's cool. 12:27 Now anyway, let's have a look at this ECG electrocardiogram. 12:36 From the P wave to the R wave, we have the atrial depolarization, but we can 12:43 even say 12:44 ventricle diastole, when essentially the right and left atrium fills, contracts 12:52 and 12:52 fills the ventricles with blood. 12:55 Then from the R wave, when it drops to the S, we have isovolemic contraction. 13:04 This is when the valves between the atrium and ventricles close and the ventric 13:10 les are 13:11 contracting, but the valves out of the heart are not open. 13:17 So the ventricles are getting ready to inject blood with force out of the heart 13:23 . 13:24 And from S to the T wave, we have ventricle injecting the blood out. 13:31 So like just still with the contraction force that it had from the isovolemic 13:37 contraction. 13:39 From the tip of the T wave to the bottom of the T wave, this phase is known as 13:45 isovolemic 13:46 relaxation. 13:47 So essentially the ventricles relax without being filled with blood. 13:52 So both of the valves from the atrium and out of the heart are closed. 13:58 I hope this is not too confusing. 14:00 Essentially, after the end of T, we have the ventricle diastole, when the vent 14:04 ricles are 14:05 being filled with blood again. 14:08 And from the P wave, we have the same process. 14:11 We have atrial systole, atrial depolarization, where the ventricles are being 14:17 filled with 14:18 blood from the atrial muscles contracted. 14:23 So we can see where atrial systole is. 14:26 We can see where ventricle systole and diastole is, but where is atrial diast 14:32 ole? 14:32 Well, it's actually behind this QRS wave here. 14:37 And it's not that visible because it's not as prominent or not as strong as the 14:43 ventricular 14:44 systole. 14:45 I hope that makes sense. 14:48 So from this diagram, we can simplify it by specifically looking at the ventric 14:53 le systole 14:54 and diastole only. 14:56 So from the R to the T wave, we have systole, ventricle contraction. 15:02 And the other is on the other sides, we have ventricle diastole, when the vent 15:08 ricles are 15:08 filling with blood. 15:13 So again, we can even make this more simple by drawing the actual action 15:18 potential of 15:18 the ventricle myoside. 15:21 So if you remember how it looks like, it can start from just after the Q, it'll 15:26 go up 15:26 and go all the way to T. So this whole duration is when the ventricle is 15:30 contracting and then 15:31 slowly we're just about to relax. 15:34 And then we can also draw the atrial myoside contraction. 15:37 And that begins in the P wave because that's atrial systole, remember? 15:41 So I hope from this diagram it kind of makes sense when it's happening. 15:46 It might be a bit complicated, so hopefully in the next video, I'll draw a 15:50 heart and draw 15:50 what actually happens in the heart during each of these intervals, between the 15:56 P and 15:56 the R wave, et cetera, et cetera.