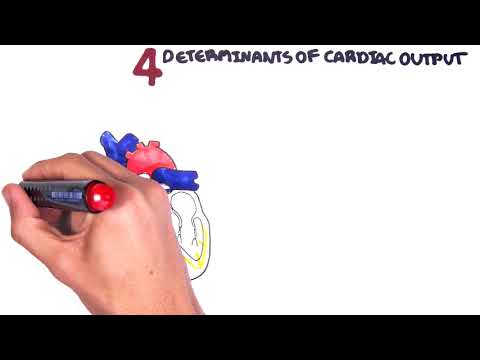

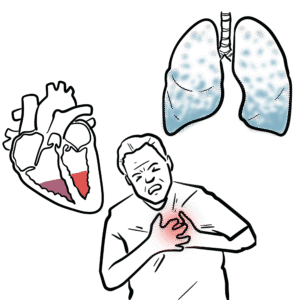

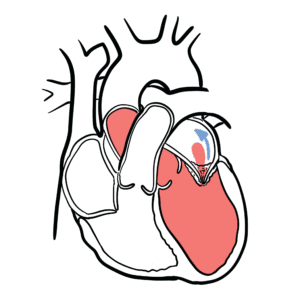

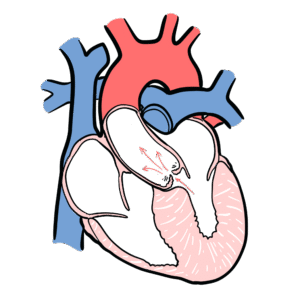

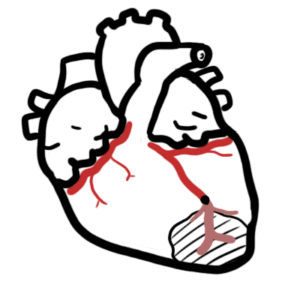

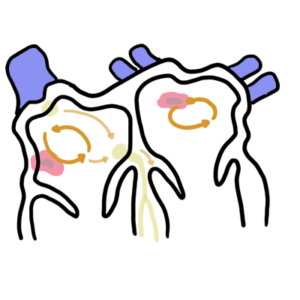

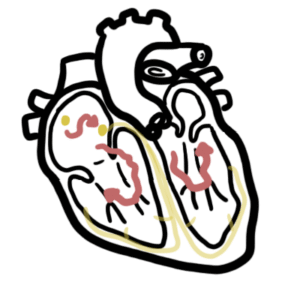

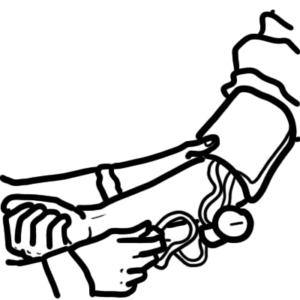

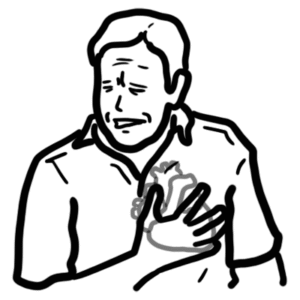

0:00 Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening condition characterized by the 0:10 accumulation 0:10 of pericardio fluid in the pericardio space. 0:16 The pericardium is layers which envelope the heart. 0:20 When fluid increases in the pericardium rapidly, it compresses all heart 0:27 chambers in that it 0:28 will impair venous return to the heart. 0:31 Essentially, filling of the heart is decreased, resulting in a reduced cardiac 0:39 output, and 0:40 in later stages obstructive shock. 0:47 Let us learn about the anatomy and function of the normal pericardium. 0:51 Here is a normal chest x-ray and here sits the heart. 0:56 The heart is enveloped by the pericardium. 0:59 The pericardium is made up of two main layers, a thin internal layer known as 1:04 the serous pericardium, 1:07 which forms the visceral and parietal pericardium, and the second is the outer, 1:13 tough external 1:14 layer known as the fibrous pericardium. 1:20 The pericardium contains a small amount of serous fluid, which allows friction 1:24 less cardiac 1:24 movement. 1:26 The pericardio sac can also adapt to changes in the heart size, as it fills, 1:32 for example. 1:34 The pericardium functions to provide a protective environment for cardiac 1:39 functions, essentially 1:41 also like a barrier. 1:44 The fluid in the pericardium can accumulate, and there are many causes. 1:49 When this happens, it is called pericardiole fusion. 1:53 A pericardiole fusion may progress to a cardiac tamponade, which is where a per 1:59 icardiole 2:00 fusion is symptomatic. 2:04 The causes of pericardiole fusion include accumulation of blood in the pericard 2:09 io sac, 2:10 following a ruptured myocardium after a myocardiole infarction. 2:15 Any organisms, be it bacteria or viruses, can also cause inflammation of the 2:20 pericardium. 2:21 This is termed pericarditis, and will cause accumulation of fluid within the 2:26 pericardiole 2:27 space. 2:29 Other vascular causes of pericardiole fusion include aortic dissection and aort 2:37 ic rupture. 2:38 Malignant cells can infiltrate the pericardium, causing a malignant pericardio 2:44 le fusion. 2:45 The therapy, as in radiation, can also damage the pericardium, causing pericard 2:52 iole fusion. 2:53 Interestingly, autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythmatosis and 2:59 sarcoidosis, 3:00 is also associated with effusions in the pericardium. 3:05 Very important, trauma, whether it be a blunt or penetrating injury, can lead 3:11 to obvious 3:12 effusions, accumulating in the pericardiole sac from damage to the heart, or e 3:17 atrogenic 3:18 causes such as following a cardiothoracic surgery, such as a coronary artery 3:24 bypass procedure. 3:28 Certain medications can also cause pericardiole fusions, there's cyclosporins, 3:33 hydrolysine 3:34 and isoniazids, which have been associated with pericardiole fusions. 3:40 Pericardiole fusion, as mentioned, can progress and become a cardiac tamponade. 3:45 It is actually not only the amount of fluid you need in the pericardium to 3:50 cause a tamponade, 3:52 but also how fast the fluid accumulates. 3:56 An acute pericardiole fusion is life-threatening. 4:00 A chronic, slow accumulation of pericardiole fluid is benign, but may 4:06 eventually manifest 4:07 with symptoms as it grows. 4:11 Here is a chest x-ray of the same person who has developed cardiac tamponade. 4:15 Note the large heart size now. 4:18 Going over the pathophysiology, when you have increase in fluid in the pericard 4:22 iole space, 4:23 there is increase in pressure against all four chambers of the heart, including 4:27 the two 4:28 ventricles. 4:29 This means the ventricles can expand during diastole. 4:32 They have a fixed ventricular volume, meaning the preload is reduced, which is 4:37 the amount 4:37 of blood returning to the heart. 4:40 As a result, chronic tamponade causes impairment of right ventricular filling, 4:46 causing signs 4:46 of right-sided heart failure, because everything gets pushed back essentially. 4:55 Examples of right-sided heart failure include elevated jugular venous pressures 5:00 , petal edema, 5:02 and acites. 5:03 Cardiac tamponade also results in impairment of left ventricular filling, 5:07 causing left-sided 5:08 heart failure, which is essentially a decrease in cardiac output. 5:12 A decrease in cardiac output causes low blood pressure as well as dyspnea. 5:18 A significant decrease in cardiac output causes shock, in this case obstructive 5:23 or cardiogenic. 5:24 And, of course, if you oscillate this area, because of all that fluid around 5:32 the heart, 5:33 the heart sounds are muffled. 5:36 An important thing to understand relating to cardiac physiology here is, 5:42 cardiac output 5:43 is equal to heart rate by stroke volume. 5:47 Preload is a determinant of stroke volume, and so is afterload and contract 5:52 ility. 5:53 A reduced preload, as seen in cardiac tamponade, will cause a reduced stroke 5:59 volume, and thus 6:00 a decrease in cardiac output, based on this simple equation. 6:10 The most important clinical manifestation of cardiac tamponade is a triad of 6:14 distended 6:14 jugular venous pressure, low blood pressure, and muffled heart sounds. 6:20 This triad is called Bex triad, first described by Claude Beck in the 1930s, 6:27 and it was specifically 6:28 used to describe acute cardiac tamponade. 6:33 Claude Beck actually described a second triad for chronic tamponade, which 6:38 involves ascites. 6:41 Other clinical features of cardiac tamponade include tachycardia, tachypnea, 6:47 pericardial 6:48 rub, if pericarditis is involved, pulsus paradoxus, and cosmal sine, which is 6:55 usually seen in 6:58 something called constrictive pericarditis, rather than cardiac tamponade. 7:06 Cosmal sine is actually very interesting and an important clinical examination 7:11 finding. 7:12 Cosmal sine is present when, during inspiration, the person's neck veins bulge 7:19 and distend, 7:21 rather than collapse. 7:24 Cosmal sine is a typical feature of constrictive pericarditis, but can also be 7:30 seen in cardiac 7:31 tamponade. 7:33 Normally during inspiration there is an increased filling in the right side of 7:37 the heart due 7:39 to a decrease in intrathoracic pressure. 7:43 This increased filling to the right side of the heart normally collapses the 7:47 neck veins. 7:50 In constrictive pericarditis there is restricted filling, and so you get the 7:55 distended neck 7:56 veins instead. 8:02 Another very important clinical finding in cardiac tamponade is pulsus paradox 8:07 us, which 8:08 is defined as an abnormal inspiratory decrease in systolic blood pressure of 8:11 greater than 8:12 10mm mercury. 8:16 Normally during inspiration there is an increased filling to the right side of 8:21 the heart, and 8:21 again this is because intrathoracic pressure decreases with inspiration, 8:25 allowing more 8:26 fluid to move inside. 8:30 The increased volume to the right ventricle during inspiration will cause inter 8:35 ventricular 8:36 septum to bulge to the left. 8:39 The bulge of the septum to the left ventricle results in a slightly decreased 8:43 left ventricular 8:44 filling volume, and therefore slightly decreased systolic blood pressure. 8:49 But this doesn't really have much of an impact normally, because there is the 8:55 ability of 8:55 the left ventricle to expand in the pericardium to compensate for the septal 9:03 shift. 9:04 During expiration the opposite occurs, there is bulging to the right side. 9:16 The arterial blood pressure traces an accurate measurement of a person's blood 9:20 pressure. 9:21 It shows you the pressure in the arteries during systole and diastole. 9:27 In a normal person during inspiration there is a subtle change in systolic 9:32 blood pressure, 9:34 usually no more than 5mm mercury. 9:39 You can experiment with this physiological mechanism by feeling your own pulse. 9:43 If you feel your pulse right now and take a deep breath in, you might notice it 9:48 to become 9:49 softer when compared to expiration. 9:55 In cardiac tamponade there is restriction in ventricular filling. 9:59 With inspiration there is significant interventricular septal bulge to the left 10:04 , decreasing left ventricular 10:05 filling volume, causing a reduction in cardiac output, and systolic blood 10:14 pressure. 10:15 With expiration the interventricular septal bulges to the right, increasing 10:24 cardiac output. 10:26 If you look at a arterial blood pressure trace of someone with cardiac tampon 10:31 ade, what you 10:32 might see is a wandering baseline. 10:35 During inspiration there is a big difference in systolic blood pressure. 10:40 This paradoxes is when this change is more than 10mm mercury. 10:48 Investigations that can be ordered for someone with a cardiac effusion or tamp 10:53 onade include 10:54 chest x-ray, which we have seen. 10:57 The heart is obviously grossly enlarged and tamponade. 11:01 ECG will show something called electrical alternates, which is alternating wave 11:08 forms. 11:08 The QRS is big and small, and this is due to the pericardial fluid encasing the 11:14 heart 11:15 and the electrical activity that is received by the ECG during this measurement 11:22 . 11:23 An echocardiogram is useful in assessing and quantifying the amount of pericard 11:28 ial effusion 11:29 and the impact it has on other organs, including backflow. 11:36 Other investigations include blood tests to help identify the potential causes 11:40 of the 11:40 pericardial effusion, including troponin to look for myocardial infarction and 11:45 odoe immune 11:46 screen. 11:50 Cardectamponade is a life-threatening condition. 11:54 Management is emergency drainage via pericardiocentesis, where a needle is 12:02 essentially stuck 12:02 in the pericardial space and the fluid is drained out. 12:11 After this treatment, the underlying cause of the effusion is then investigated 12:16 and managed. 12:18 Thank you for watching. 12:19 I hope you enjoyed this video. 12:32 [BLANK_AUDIO]